Budleigh in Books: Part 2

[Click http://budleighbrewsterunited.blogspot.co.uk/2014/07/budleigh-in-books-part-i.html to read Budleigh in Books Part 1 ]

One of Grainger’s many books, The Solutions of Radford Shone was published by Ward Lock in 1908 Image credit: http://www.batteredbox.com

I reckon that Budleigh makes a good

setting for crime thrillers. Plenty of Colonel Mustards - well, not so many

nowadays, perhaps. Arsenic, maybe, and certainly masses of old lace in Fairlynch Museum.

Lots of possibilities of suspicious drownings, riding accidents and falls from

the cliffs.

Francis Edward Grainger thought so anyway. The son of a clergyman, he had an army career before finding his vocation as an author and journalist. He lived at various addresses in Budleigh Salterton, including ‘Almora’ at 33 Station Road, at Sherbrook Lodge and on Marine Parade.

He died in Budleigh in 1927 at the age of 70 after writing more than 60 detective stories and romances using the pen name Headon Hill. They had titles like Clues From a Detective's Camera (1893) and Zambra the Detective (1894). His character Sebastian Zambra was a consulting detective similar to Sherlock Holmes who appeared in a number of short stories and novels. One of his books was The Cliff Path Mystery (1922) based on a suspicious fall from the cliff path just behind the house 'Broomleas' at the top of Victoria Place.

The

boys’ class of Park

House School,

Knowle, in around 1910. The young Clinton-Baddeley can be seen far right. Image

credit: Fairlynch

Museum neg 1/C/3/24a

The

boys’ class of Park

House School,

Knowle, in around 1910. The young Clinton-Baddeley can be seen far right. Image

credit: Fairlynch

Museum neg 1/C/3/24a

He was born on 30 May 1900 into a well-connected family possibly descended from General Sir Henry Clinton (1730-95) who served for a time as Commander-in-Chief of British forces during the American War of Independence.

After reading History at Cambridge University, he made his debut as an author at the age of 25 with a book entitled simply Devon. The publishers, A. & C. Black Ltd, judged it fine enough to be illustrated by Sutton Palmer (1854-1933), a noted watercolour artist who specialised in idyllic rustic landscapes. A second edition appeared three years later in 1928. The book reveals the author's fascination with the region's history and landscape, including observations on witchcraft and local superstitions.

This photo from a 1937 edition of the Radio Times shows Clinton-Baddeley outside a studio where he had just finished giving a television reading from A.A. Milne. Unluckily for him the BBC fireman was patrolling the studio corridors just at that moment, enforcing the 'No-Smoking' rule Image credit: Radio Times

The book that he was apparently most proud of was The Burlesque Tradition in the English Theatre after 1660, published in 1952. This was a study of what the author called the “friendly humour” of theatrical burlesque as distinct from the “zeal of satire and the malice of satire.” Writers quoted included Shakespeare, John Gay, Henry Fielding, Bernard Shaw, Max Beerbohm and Stephen Leacock.

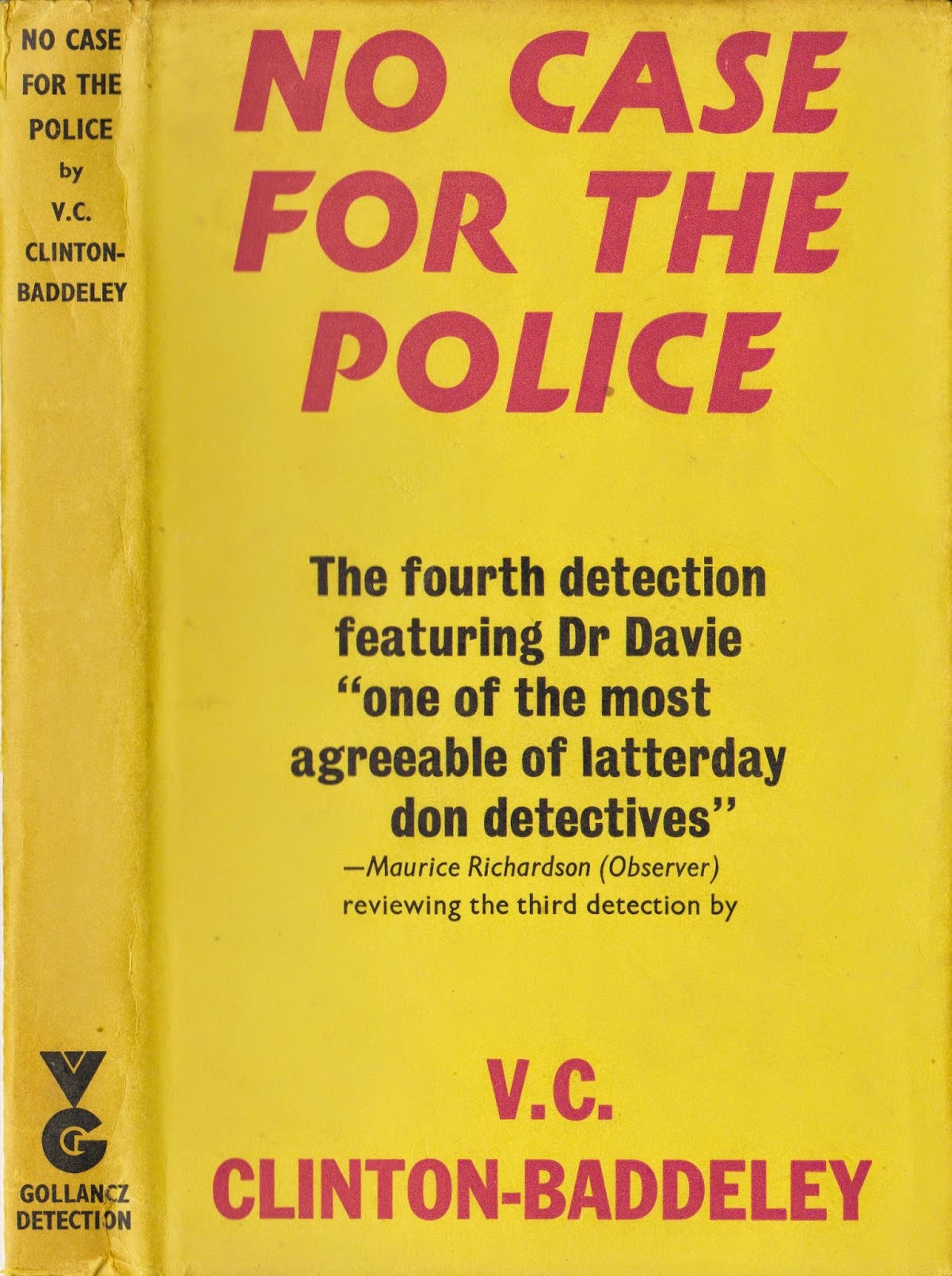

No case for the Police was published in 1970. By coincidence, two years earlier, the reviewer, Maurice Richardson, had written about his prep school and childhood memories of Budleigh Salterton in a book entitled Little Victims. Like Clinton-Baddeley he also lived for a time in Budleigh Salterton

Towards the end of his life Clinton-Baddeley took to composing crime fiction. It’s his detective novel No Case for the Police that really uses local colour to portray what we know to be Budleigh Salterton in a fictional setting. Clinton Baddeley’s detective hero is called Dr Davie, an Oxford academic who enjoys solving puzzles. In No Case for the Police he goes back to the village of his youth to attend the funeral of one of his oldest friends.

There are various name changes: Budleigh Salterton becomes Tidwell St Peter’s; The Rolle Arms - once one of the area’s grandest hotels but now sadly demolished and transformed into a block of flats - becomes The Ottery Arms.

The Stone Garden today in Bicton Park, composed, according to Clinton-Baddeley, of rocks removed from an East Devon neolithic circle.

Across the road in the novel stood "the rival hall, the Gospel Hall, red brick, unadorned, not a slate out of place, not a laurel leaf missing," exactly as the Evangelical Church stands today in Budleigh. Only in the last few years has its name been changed to 'The Church on the Green.'

Other little local touches include the chiming of the clock on the Methodist church, “Fore Street, where the brook so delightfully emerges from beneath the houses, and babbles along beside the street to the sea”, the footpath to West Down beacon past the Chine and what is now Jubilee Field, stones from the beach used as door stops - though Davie frowns on the practice; even the naturist beach gets a mention.

Sir John Everett Millais painted 'The Boyhood of Raleigh' during his stay in The Octagon, on Budleigh Salterton's sea-front in 1870

There’s an obvious reference to Millais’ painting 'The Boyhood of Raleigh' - famously set on the sea-front in Budleigh - but the Victorian artist is renamed by Clinton-Baddeley as Ambrose Faddle. A detail in Millais’ painting is seized on by the author to portray the drug-smuggling character Walter Ford in No Case for the Police.

“In the manner of an earlier age, he actually wore little gold earrings in his ears," the narrator tells us. "If he had claimed to be the original sailor in Ambrose Faddle’s masterpiece the visitors would hardly have disbelieved him: and in fact his great-grandfather had been the very man.”

Clinton-Baddeley’s use of local colour is truly intense in No Case for the Police. This Budleigh-born author may poke gentle fun at the town of his birth - much in the manner of his artist friend Joyce Dennys - but the intimacy of his brush strokes may owe much to nostalgia.

It’s ironic that this novel in which Clinton-Baddeley's hero Dr Davie comes back home appeared in the year of the author’s death, in 1970.

It’s almost as if he knew that his own return was imminent.

And indeed he’s buried in the family vault in the picturesque setting of East Budleigh churchyard.

To read Part 3 of Budleigh in Books, click here

Francis Edward Grainger thought so anyway. The son of a clergyman, he had an army career before finding his vocation as an author and journalist. He lived at various addresses in Budleigh Salterton, including ‘Almora’ at 33 Station Road, at Sherbrook Lodge and on Marine Parade.

He died in Budleigh in 1927 at the age of 70 after writing more than 60 detective stories and romances using the pen name Headon Hill. They had titles like Clues From a Detective's Camera (1893) and Zambra the Detective (1894). His character Sebastian Zambra was a consulting detective similar to Sherlock Holmes who appeared in a number of short stories and novels. One of his books was The Cliff Path Mystery (1922) based on a suspicious fall from the cliff path just behind the house 'Broomleas' at the top of Victoria Place.

Image

credit: The Shirburnian

Among the

many authors who’ve lived in Budleigh Salterton, V.C. Clinton-Baddeley stands

out as someone who was not only born in the area but wrote about it, used it as

a literary setting and found his last resting-place here.

The

boys’ class of Park

House School,

Knowle, in around 1910. The young Clinton-Baddeley can be seen far right. Image

credit: Fairlynch

Museum neg 1/C/3/24a

The

boys’ class of Park

House School,

Knowle, in around 1910. The young Clinton-Baddeley can be seen far right. Image

credit: Fairlynch

Museum neg 1/C/3/24aHe was born on 30 May 1900 into a well-connected family possibly descended from General Sir Henry Clinton (1730-95) who served for a time as Commander-in-Chief of British forces during the American War of Independence.

Image

credit: The Shirburnian

After reading History at Cambridge University, he made his debut as an author at the age of 25 with a book entitled simply Devon. The publishers, A. & C. Black Ltd, judged it fine enough to be illustrated by Sutton Palmer (1854-1933), a noted watercolour artist who specialised in idyllic rustic landscapes. A second edition appeared three years later in 1928. The book reveals the author's fascination with the region's history and landscape, including observations on witchcraft and local superstitions.

The second

chapter 'A Corner of the Country' is evidently inspired by his exploration of

the countryside around Budleigh Salterton with its mention of Sir Walter

Raleigh's birthplace at Hayes Barton. The final fifth chapter describes a

200-mile cycle trip that he made, starting in what he calls the

"weird" marshlands of the Otter

Valley, and ending at

what is clearly his home town where he hears "the waves breaking on the

beach below the sandstone cliffs."

This photo from a 1937 edition of the Radio Times shows Clinton-Baddeley outside a studio where he had just finished giving a television reading from A.A. Milne. Unluckily for him the BBC fireman was patrolling the studio corridors just at that moment, enforcing the 'No-Smoking' rule Image credit: Radio Times

Like his

cousins Angela and Hermione, Clinton-Baddeley himself was deeply involved with

the theatre in his lifetime, both as an actor and playwright, author of 15

plays, one screenplay and various pantomimes.

He also made his mark in broadcast media. He gave his first BBC

performance - a prose reading - in 1928. Two years later, from January to April

1930, the first serial adaptation of any Dickens novel on radio was

transmitted, when he read Great

Expectations as a solo turn in sixteen instalments.

The book that he was apparently most proud of was The Burlesque Tradition in the English Theatre after 1660, published in 1952. This was a study of what the author called the “friendly humour” of theatrical burlesque as distinct from the “zeal of satire and the malice of satire.” Writers quoted included Shakespeare, John Gay, Henry Fielding, Bernard Shaw, Max Beerbohm and Stephen Leacock.

No case for the Police was published in 1970. By coincidence, two years earlier, the reviewer, Maurice Richardson, had written about his prep school and childhood memories of Budleigh Salterton in a book entitled Little Victims. Like Clinton-Baddeley he also lived for a time in Budleigh Salterton

Towards the end of his life Clinton-Baddeley took to composing crime fiction. It’s his detective novel No Case for the Police that really uses local colour to portray what we know to be Budleigh Salterton in a fictional setting. Clinton Baddeley’s detective hero is called Dr Davie, an Oxford academic who enjoys solving puzzles. In No Case for the Police he goes back to the village of his youth to attend the funeral of one of his oldest friends.

There are various name changes: Budleigh Salterton becomes Tidwell St Peter’s; The Rolle Arms - once one of the area’s grandest hotels but now sadly demolished and transformed into a block of flats - becomes The Ottery Arms.

Lady Ottery, in the novel, is therefore Lady Rolle. Here's

Davie's and

evidently Clinton-Baddeley's disparaging reference to the nearby settlement of

Bicton:

The Stone Garden today in Bicton Park, composed, according to Clinton-Baddeley, of rocks removed from an East Devon neolithic circle.

“‘It's a pity about the church,’ said Davie, pointing up the valley towards a

village in a mist of trees. One of Lady Ottery's nineteenth-century outrages.

The old gorgon pulled down a fourteenth-century church and put up that wholly

improbable granite affair to the greater glory of Lady Ottery. I believe she

also removed a neolithic circle from the moor to make a rockery in her

garden.'” See http://www.branscombe.net/Branscombe%20parish/Branscombe%20Parish%20-%20Prehistory%20and%20the%20Celtic%20Heritage.htm

The

names may have been changed but the geographical setting is very clear. We have

the same sardonic reference to Budleigh’s negative image in Clinton-Baddeley’s

book that characterised R.F. Delderfield’s portrayal of Pebblecombe Regis. The

two authors may have known each other; they certainly had a mutual acquaintance

in Joyce Dennys.

Here is Dr Davie arriving by bus on the

outskirts of his home town:

“First

the pine woods, then the beech woods. And then, as the road

levelled out at the

bottom of the

hill, the first houses, and a

sign which bade

the visitor 'Welcome to Tidwell St Peter's'.

Davie wondered

a little about that.

As he remembered the village, visitors had never been in

the least welcome - except

to those who

catered for them.

Sixty years back, when the motor car had been a rarity

and the aeroplane unknown, the place had been a jealously preserved haunt of

retired colonels and

demoted memsahibs, who,

leaving behind them a life

of oriental splendour, of turbaned

servants, elephants who

raised a military

trunk to the

right people, tiger hunts,

polo, tennis, amateur

theatricals at Simla, had

somehow contrived in more straitened circumstances to live a life of

dignity among the

pine trees and

rhododendrons, still largely concerned

beneath softer skies with the propulsion

of balls, golf, tennis, cricket and

croquet. lndeed the more whimsical ones, inspired by legends of Drake, obtained some

mastery over the

biassed wood. Tidwell St Peter's

is still a

place of retirement

for the distinguished old, and in varying parts of the parish a variety of balls still smack, click, or

thud, over or into

the net, the marshes,

the bunker, the

gorse and the heather. But backgrounds

are different. There are

fewer memories now of

Naini Tal and

Peshawar, more of

Manchester and Golders Green.

And now there

were houses and gardens on

both sides of the road, and presently the

golf links on

the right and a pine

wood on the

left, and then the

road dipped down again for the final descent to the sea.”

The

first lines of No Case for the Police

describe the western approach to the town along Exmouth Road, with its "distant

glimpses of the sea" and the railway bridge over the disused line

"already overgrown" through the sandstone cutting. A few minutes

later, the reader is told of "that turning to the left which led to Davie's old home" and

which can only be Budleigh's Station

Road, where the Clinton-Baddeley family home

'Wairoa' was situated. It's there, by Tidwell St Peter's village hall, that the

bus comes to the end of its run, just as today's 357 service stops outside

Budleigh's Public Hall before its return to Exmouth.

Across the road in the novel stood "the rival hall, the Gospel Hall, red brick, unadorned, not a slate out of place, not a laurel leaf missing," exactly as the Evangelical Church stands today in Budleigh. Only in the last few years has its name been changed to 'The Church on the Green.'

In

a further clue to the heavy autobiographical element in No Case for the Police, as he stands gazing at the Gospel Hall the

sound of its congregation reaches his ears through memories of more than half a

century. "Dear God!" he reflects. "How those Bretheren used to

sing!"

"Long

ago, as a prejudiced son of the Anglican church, Davie had thought them comical, those earnest

voices yearning for the new Jerusalem. He did not think so now."

Clinton-Baddeley, of course, was the son of a vicar.

The negative touches continue, I’m afraid: Tidwell

St Peter’s is described as "an old-world resort", a place "full

of people honourably retired from running the world and without the smallest

intention of running anything more exhausting than the bridge club."

“Everyone lives to be a hundred and two here,” remarks

Irene, one of his characters, “but most of them can’t move after the age of

ninety.”

Davie is shown

“smiling to himself over ‘the older residents’ and their notorious prejudices.”

We smile with him at all the little observations so familiar to us readers ‘in

the know’ who love our little town with all its foibles. “If you knew people in

Tidwell St Peter’s it was impossible to make your way without a constant

repetition of ‘Morning,’ and ‘Another lovely day’ and all those other passwords

which enable people to pass. The street was

abuzz with aimiable comments about the weather.”

Other references to Budleigh Salterton abound, including a

reference to the passing of the great days of mackerel fishing, worthy of a

place in Fairlynch

Museum’s archives for its

vividness:

"When

I was a boy,” recalls one of the local residents whom Davies meets, “the

fisherman used to sit up here and watch the sea for the shoals, and suddenly

one of them would cry out and point at a glittering in the water, and they'd

all rush down to the beach and jump into a boat and row out in a circle, paying

out a net. It would be quite close to shore." He goes on to remember how

he with other children would help pull in the net. "And when the haul was

landed we used to be given a fish for our services."

Other little local touches include the chiming of the clock on the Methodist church, “Fore Street, where the brook so delightfully emerges from beneath the houses, and babbles along beside the street to the sea”, the footpath to West Down beacon past the Chine and what is now Jubilee Field, stones from the beach used as door stops - though Davie frowns on the practice; even the naturist beach gets a mention.

It’s

not too fanciful to identify a particular shrub described in No Case for the Police with the

present-day specimen. As Davie heads towards

Rose Cottage, described as "fifteen minutes' walk from the Ottery Arms,

along the Exeter

road and then down the hill on the right by the little common and the fir

wood" he passes a garden on the right where there was an enormous

rhododendron. "It had been there ever since Davie could remember. It was a deep rose

colour and was always out a fortnight before any other rhododendron in Tidwell

St Peter's." And so it is

today, blooming as vigorously and even more enormous, on the corner of West

Hill and Meadow Road.

Sir John Everett Millais painted 'The Boyhood of Raleigh' during his stay in The Octagon, on Budleigh Salterton's sea-front in 1870

There’s an obvious reference to Millais’ painting 'The Boyhood of Raleigh' - famously set on the sea-front in Budleigh - but the Victorian artist is renamed by Clinton-Baddeley as Ambrose Faddle. A detail in Millais’ painting is seized on by the author to portray the drug-smuggling character Walter Ford in No Case for the Police.

“In the manner of an earlier age, he actually wore little gold earrings in his ears," the narrator tells us. "If he had claimed to be the original sailor in Ambrose Faddle’s masterpiece the visitors would hardly have disbelieved him: and in fact his great-grandfather had been the very man.”

Clinton-Baddeley’s use of local colour is truly intense in No Case for the Police. This Budleigh-born author may poke gentle fun at the town of his birth - much in the manner of his artist friend Joyce Dennys - but the intimacy of his brush strokes may owe much to nostalgia.

It’s ironic that this novel in which Clinton-Baddeley's hero Dr Davie comes back home appeared in the year of the author’s death, in 1970.

It’s almost as if he knew that his own return was imminent.

And indeed he’s buried in the family vault in the picturesque setting of East Budleigh churchyard.

To read Part 3 of Budleigh in Books, click here

Comments

Post a Comment