Budleigh Salterton scientist Henry Carter and that dinosaur poo

At a previous

post about Fairlynch’s Object of the Month for April 2016 I promised that I

would give some background to my pooem at http://budleighbrewsterunited.blogspot.co.uk/2016/04/fairlynch-museums-object-of-month-for.html

No, it wasn’t

an April Fool.

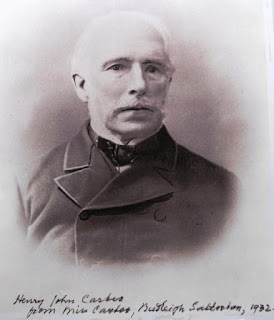

A few years

ago I wrote the first biography of any length devoted to the life and

achievements of Henry Carter FRS, physician, geologist and naturalist, pictured above.

Born in

Budleigh Salterton, Carter returned to his “native place” as he calls it in

1862 after travels in Arabia and working as a doctor in India East Budleigh .

Carter was

internationally known by his contemporaries for his research into marine

sponges, but it was for his work as a geologist that the Royal Society elected

him as a Fellow in 1859.

There is

evidence to show that his geologising had begun while he was still a boy, as he

explored the coastline around Budleigh Salterton. In fact, in a 1981 article

published in the Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural

History) Geology Series, Dr

Robin Cocks of the Natural History Museum’s Palaeontology

section, mentioned that it was a Mr Carter who had found brachiopod fossils in

Budleigh pebbles in around 1853. From

my research into Carter’s life I concluded that the fossil Orthis budleighensis should be renamed Orthis carteri.

In 1859,

while Carter was still in India

Given his

many years of geologising in the sub-continent it is highly likely that Carter,

on his return to Britain, would have been motivated to search in the area east

of the River Otter where the rhynchosaur remains had been found, particularly

as Huxley had in his paper referred to some specimens obtained from Central

India, among which "were fragments of large jaws with teeth, which

presented all the characters of Hyperodapedon."

At any rate

Carter is noted as having found "many traces of osseous structure at this

locality" according to later geologists Horace Woodward (1848-1914) and

William Ussher (1849-1920). He may even

have noted in Huxley's article the fact that the fossils had been presented to

the Geological Society in 1860 by Stephen Hislop, whose work in India

A later event of interest to Carter was the discovery

in 1875 of bones identified as those of a labyrinthodont. This carnivorous

amphibian is thought to have flourished in the late Carboniferous/early Permian

— approximately 260 million years

ago. The find was made in fallen debris from the cliffs between Budleigh

Salterton and Sidmouth by Henry James Johnston-Lavis (1856-1914), a Devonshire man who like Carter had trained as a physician

at University College London, where he also studied geology. He was later noted

as a volcanologist.

Woodward and Ussher noted that Carter

"subsequently obtained bone structures of Labyrinthodont affinities, and a

fragment of jaw-bone, with teeth" from the same location below the western

slope of High Peak Hill at Picket Rock Cove.

Evidently the

71-year-old Carter, who by this time was primarily concerned with his work of

cataloguing sponges, continued to be intrigued by such finds so close to his

home. A further paper on the fossil remains in this location west of High Peak

Hill appeared in 1884, authored on this occasion by Arthur Metcalfe

(1857-1938). Born in Retford, near Nottingham ,

he began studying geology as a schoolboy and was elected a Fellow of the

Geological Society of London at the age of 23.

It is notable that in publishing his research findings concerning the

vertebrate remains discovered in the Triassic sandstone strata east of Budleigh

Salterton Metcalfe was proud to acknowledge the role of his "friend"

Henry Carter in obtaining the "rare and interesting specimens" now in

the Natural History Museum

Carter was

keen to carry out his own research into the fossils. He had discovered what he

described as "small pellet-like amorphous bodies" among the fallen

blocks of Triassic rock on the beach where the Labyrinthodont

remains had been found. They were, he observed, "composed of

white calcareous matter, traversed in all directions by semitransparent

crystalline plates showing bone-structure" and were identified as

coprolites, the scientific term used to describe the fossilised dung of ancient

animals.

He found that

sections of the coprolites, "when examined in water under the microscope,

presented the same bone-structure as the scales of the Bony Pike of North

America (Lepidosteus osseus)."

This was confirmed when he compared a fossilised pike scale found in Hampshire

to a similar fragment of the fossil from the East Devon

beach. In 1888 the Geological Society

published his short account of how this ancient dung from a fish-eating

creature from 200 million years ago could be described as "Ichthyosaurian

coprolites."

These fossils described by Metcalfe and Carter have been written of as "fragmentary and

unpromising." But the

evidence of Carter's involvement in geology at this late stage in his life is

nonetheless of value, if only to Devon

historians. Metcalfe's account shows the high regard in which Carter was held

by a geologist who was less than half his age in 1888. And it proves that the

older man retained a continuing interest in the county's ancient landscape for

as long as his considerable powers of intellect would allow.

On 4 October that year Henry Carter suffered a

paralytic attack which left him with impaired speech and vision. He improved

but never completely recovered.

Comments

Post a Comment