WW2 75.4 Resentment or Reconciliation? The problem of Japan

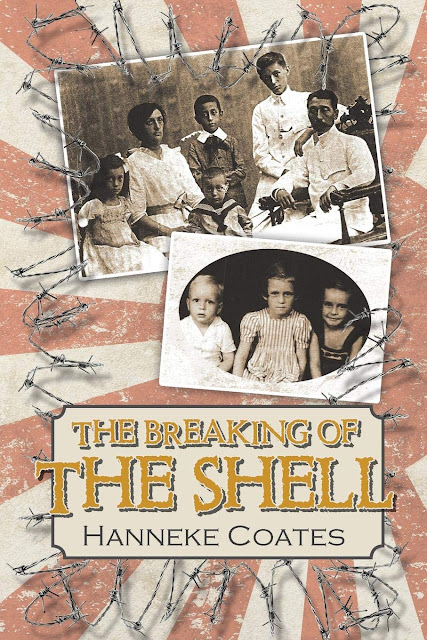

The Breaking of the Shell by Hanneke Coates, survivor of a WW2 Japanese internment camp, now living in Yettington, near Budleigh Salterton

Today is the 75th anniversary of the dropping of the atomic bomb on Nagasaki, and this Saturday 15 August is VJ Day or Victory over Japan Day. It marks the moment when Imperial Japan surrendered in World War Two, in effect bringing the war to an end.

The surrender meant relief and freedom for thousands of Allied prisoners of war. But coming as it did after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, VJ Day was and will always be a bitter-sweet reminder of the evil of war and nuclear weapons, especially

when used against a civilian population.

In 2018, Yettington resident Hanneke

Coates published an account of her experiences as a prisoner of the Japanese in

World War Two, and an explanation of how she has come to terms with that awful

time.

As a boy growing up near Highbridge,

a small town in Somerset, I remember being struck that the owner of the local

electrical shop refused to sell any Japanese goods. Heads nodded silently in sympathy

when customers heard about his stand. Later, I learnt of the horrors of the

Burma Railway, and of the savagery that Allied soldiers – including my father –

used against Japanese troops in the jungles of the Far East during World War

Two.

Many years later, to mark the 50th

anniversary of the end of the War, I decided to write my own book about its

impact on the Northamptonshire town of Oundle where I was living, and about

life in the 1939-45 period.

Former captor and captives at the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Yokohama.

Photo from Big Story

© Carlton UK Television

It was moving and heartening to

discover this photo which I used in my book. Taken in 1995, it shows two former

PoWs, James Bradley MBE, and Douglas Weir, who had suffered terribly at the

hands of the Japanese in their prison camp. Their former guard, the repentant

war criminal Hiroshi Abe, is alongside them.

For my own book which I was

writing at around that time, James Bradley kindly allowed me to quote

extensively from the account of his experience as a PoW. His book, Towards the Setting Sun: An Escape from the Thailand - Burma Railway, 1943, had been published in 1982.

Over 12,000 Allied PoWs are said to have died

under Lt Hiroshi Abe’s supervision. After the War, he was sentenced to death by

hanging and imprisoned in Changi Prison. In 1947, his sentence was commuted to

15 years, and he was released in 1957.

Abe’s admission of guilt has been

widely quoted. ‘The construction of the railway was in itself a war crime,’ he

stated. ‘For my part in it, I am a war criminal.’

‘I can never forget the suffering

of your men when you had to burn and bury your dead’, he told James Bradley. ‘I

must take a large part of the blame for what happened.’

Tony Lloyd: MP for Rochdale since 2017

In 1995, he testified against his

own government in a lawsuit seeking compensation for Koreans in Japan during

World War Two. The following year, on 4 December 1996, Hiroshi Abe’s words were

quoted by the Labour MP Tony Lloyd in the House of Commons as follows:

‘Japan, as a nation, has not properly considered the issues surrounding

its role in the war. Japanese people do not know and do not care what happened.

Before the Japanese people can think about apologising to other countries, they

will have to acknowledge to themselves their responsibility.’

Aubrey Clarke, captured in Java, was a prisoner of

war in Japan

Aubrey Clarke, an Oundle

resident, was another British PoW whom I interviewed for the book. He surprised

me with his wartime memories. He remembered his guard as ‘quite a decent bloke’

and spoke of the boxing competition organized in his camp by the Japanese. The

enemy spectators’ reaction was unexpected. ‘Our chaps went in and thought that

if we beat them they’ll knock the living daylights out of us, but it wasn’t

like that at all,’ recalled Aubrey. ‘When our chaps were beating the Nips up,

the other Nips cheered and clapped because we were winning. It was a bit

ridiculous really.’

Aubrey even remembered acts of

kindness on the part of his guards towards their prisoners: ‘The Nips used to

come round, say, in the middle of the night to see whether you were covered up

properly, because although the temperature in the day was nearly up to 100, at

night it got down to nearly freezing and I’ve seen Nips with bayonets attached

to their rifles covering up blokes with blankets, which tells you they weren’t

as heartless as some people might imagine.’

Australian and Dutch prisoners of war, suffering

from beriberi, at Tarsau in Thailand in 1943

Unknown photographer Image credit:

Wikipedia

Geoffrey Coxhead was another Far

East PoW who had been educated in Oundle and was later captured in 1941, when

Japanese forces invaded Hong Kong, where he was a Gunner with the Volunteer

Defence Corps.

While researching material for this blog post, I discovered his

obituary, published in the October 2000 edition of the Java FEPOW Club. He’d

survived four years as a PoW to become headmaster of King's College, Hong Kong.

I thought that this passage from the obituary was worth quoting:

‘Unlike many ex-Japanese PoWs, Coxhead never

felt animosity towards his captors. He experienced sufficient acts of kindness

to appreciate the distinction between individual Japanese and their government.

On one occasion he was “resting” in the hold of a ship when he should have been

working; two guards spotted him, threw him a packet of cigarettes and walked

on. After the war, he returned three times to his place of imprisonment, and

was always given a VIP welcome by the Japanese dockyard workers.’

Newly-liberated Allied prisoners in makeshift quarters in a central corridor and from crowded cells in Changi Prison in 1945 Unknown photographer Image credit: Wikipedia

Not surprisingly, a repented war

criminal like Hiroshi Abe has not made himself popular in his homeland. But

he’s not alone in acknowledging Japan’s guilt, as Tony Lloyd reminded the House

of Commons in a statement back in 1996:

‘It would be helpful for the House to be aware that the

Government Workers Union - the largest trade union in Japan - last year gave

its support to the court proceedings of the Japanese Labour Camp Survivors Association.

The union argued that it was necessary for Japan to recognise, as a nation, its

responsibility to the former prisoners of war and urged the Government to

accept the consequences.’

The Far

East Prisoners of War Memorial Building, National Memorial Arboretum

Image credit: Chris' Buet geograph.org.uk

COFEPOW (Children and Families

of Far East Prisoners of War) is a charity, founded in 1997, which is devoted

to perpetuating the memory of such PoWs. Among its Patrons is Terry Waite CBE,

the former envoy for the Church of England who was kidnapped in Lebanon and

held captive from 1987 to 1991.

The charity successfully raised

£500,000 for the construction of the FEPOW Memorial Building which was

officially opened at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire in 2005.

I visited the Memorial Building

soon after its opening and was impressed by all the work that had gone into the

project, as well as moved by all the poignant accounts of PoWs’ experiences.

But the relentless theme of atrocious Japanese cruelty displayed throughout the

exhibitions weighed heavily on me.

I

found no mention of Hiroshi Abe, nor any record of how other Japanese

individuals in modern times have condemned the conduct of an earlier wartime

generation.

Keiko Holmes, for example, founded the charity Agape in 1996, helping to promote reconciliation between Japan and her former World War Two prisoners of war. In 1998 Mrs Holmes was awarded the OBE.

Keiko Holmes, for example, founded the charity Agape in 1996, helping to promote reconciliation between Japan and her former World War Two prisoners of war. In 1998 Mrs Holmes was awarded the OBE.

I spoke to a friend who has been

involved with COFEPOW, and who showed me round the building. I explained my

feelings. It would have been even more moving to see expressions of heartfelt

repentance from Japanese people on an exhibition panel, I suggested.

After all, COFEPOW founder Carol

Cooper has given her view of the Memorial Building in these admirable words: ‘Together

we have brought before others this poignant tragedy of war and will strive to

ensure that future generations use this knowledge to work towards global peace.’

My friend’s view was that the

organization would not support the idea of such a panel. Understandable in many

ways.

My visit to the COFEOW Memorial

Building was over ten years ago.

David’s reply earlier this month was encouraging. He mentioned the excellent work being undertaken by Keiko Holmes to foster reconciliation, and the annual event hosted by the Japanese Embassy in support of that cause. And he promised to raise my suggestion with COFEPOW Trustees at their next meeting.

David’s reply earlier this month was encouraging. He mentioned the excellent work being undertaken by Keiko Holmes to foster reconciliation, and the annual event hosted by the Japanese Embassy in support of that cause. And he promised to raise my suggestion with COFEPOW Trustees at their next meeting.

Some people may feel that no

amount of remorse can atone for terrible crimes. Others believe in the power of

forgiveness.

Hanneke Coates, pictured above, was born just before the Second

World War on the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), where

her father was a tea planter. After the invasion of Java by the Japanese in

1942, she was forced to spend three and a half years of her childhood in one of

over 300 concentration camps based around the Archipelago.

After the war, as was the practice with many

colonials, Hanneke’s parents remained abroad whilst she and her siblings

returned to Holland to be fostered out to a number of Dutch families. Later

Hanneke moved to England, where she settled in Devon.

On his way to court: Kenichi

Sonei, commander of Tjideng , the Japanese internment camp

for women and children in what was then Batavia, Dutch East Indies. ‘An

extremely unstable and violent man who turned the lives of the internees into

hell.’ He was executed on 7 December 1946

Image credit: https://nl.wikipedia.org

‘After the invasion all European women and

children were advised by the Japanese forces to move to protection camps for

their own safety,’ she recalls. ‘So we

left our homes voluntarily expecting to be protected, but as soon as the camps

were filled, they put barbed wire around us. In the meantime husbands and

fathers were sent to work on the Burma railway line or placed in concentration

camps in and around Japan.

‘We were constantly moved from one camp to

another, often transported in boarded up train carriages without seating,

lavatories, food or drink. My final camp was the notorious Tjideng camp (now

part of Jakarta) which housed around 11,000 women and children. The camp was one of many set up to intern

European civilians, mainly Dutch, as ‘Guests of the Emperor’ during the period

1942 to 1945. Those of us who ended up

there experienced what can only be called ‘hell on earth’.

‘Food was in short supply and we survived on a

starvation diet of half a coconut shell with rice and water-lily soup once a

day. Water and sanitation were almost non-existent and medical supplies very

scarce as all Red Cross parcels were withheld by the Japanese. We all suffered

from tropical diseases such as cholera, dysentery and malaria.

Women and children at roll call in

Tjideng Prison Camp were ordered to ‘Attention!’ ‘Bow!’ and ‘Stand up!’ as they

faced north towards Japan and the Emperor https://theindoproject.org

‘The most lasting effect of those three and a half

years in captivity was the relentless and total humiliation the Japanese

inflicted on us. We were day and night screamed at, publicly disgraced and

punished by having our hair hacked off with blunt knives and regularly lashed

with long whips. Many times a day we were herded on to the parade ground to

stand for hours in the burning tropical sun and to bow to our captors. One of

my earlier memories is from when I was four years old when we were made to

witness the hanging of two Dutch soldiers. By the end of the war many hundreds

of thousands of women and children had died through malnutrition, tropical

diseases and lack of medication. I was one of the lucky ones.

Internees in Tjideng

Prison Camp, Batavia, 1945 after the arrival of the Allies.

Photograph

SE 4863 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

‘In 1948 I

was sent to Holland to finish my schooling (11 schools altogether!) living with

a number of incredibly cruel foster families. As a planter, my father carried

on working first in Indonesia, then Ghana, and since European leave only came

round every four years my parents became as good as strangers to me.

‘Even though the concentration camp years had a

deep and damaging effect on us, as a family we simply did not talk about it, as

it was a taboo issue when we returned to Holland. The Dutch had endured

occupation by the Germans and suffered severe cold winters and hunger too, and

therefore they did not want to know about our suffering.

‘I thought I had forgiven my Japanese captors, and

yet was always aware of the hairs rising in the nape of my neck when I heard a

Japanese voice.

A Buddhist painting and signposts of prayer

and wish at the top of Mt. Hiyoriyama, a 6.3m high man-made hill in Natori,

Miyagi, Japan, scene of the devastation caused by the 2011 tsunami. Over 15,000 deaths were caused; over 6,000 people were injured and 2,529 were accounted as missing

Photo by Chief Hira. Wikimedia

‘The Japanese tsunami changed all that. My church

asked us to dig deep for the Japanese victims. After a lot of prayer I did just

that. It was that one last and final gesture of letting God deal with the

residue of my resentment that brought the final healing. I no longer worry

about Japanese voices now.

‘Forgiveness is a healing process and the positive

force in my life. It gives me a constant sense of peace and grace. I now share

my story in schools, churches and secular groups. Almost always someone will

share with me afterwards how my talk has changed something for them.’

You can read more about Hanneke and about her book

‘The Breaking of the Shell’ at

https://www.theforgivenessproject.com/stories/hanneke-coates/

You can access other posts on this blog by going to the Blog Archive (under the ‘About Me’ section), and clicking on the appropriate heading.

You can access other posts on this blog by going to the Blog Archive (under the ‘About Me’ section), and clicking on the appropriate heading.

Comments

Post a Comment