WW2 100 – 26 February 1944 – ‘He died that others might have a future’: Flight Sergeant Allan Edward Dearlove Davey (1922-44) Royal Australian Air Force, 90 Squadron

Continued from 29 January 1944 – ‘A very gallant old soldier’:

SERGEANT DANIEL GEORGE DICKS (1910-44)

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2021/02/ww2-75-29-january-1944-very-gallant-old.html

Allan

is the only Australian serviceman in a military grave at St Peter’s Burial

Ground in Budleigh Salterton.

Budleigh Salterton War Memorial at the junction of Coastguard Road and Salting Hill

His

name is listed on the War Memorial because his wife came from a well known

local family.

Allan’s grave in St Peter’s Burial Ground, Moor Lane, Budleigh Salterton

The Commonwealth War Graves

Commission (CWGC) record tells that he was the son of Horace Edward Dearlove

Davey (1887-1978) and his wife Floradora Stephen Mechen Davey (d.1993), and they

probably provided the personal inscription, part of which I’ve used to

introduce this post: ‘Loved and remembered fondly by his family in Adelaide

South Australia. He died that others might have a future.’

There are other poignant aspects to Allan’s story, some absent from the CWGC record, which I discovered, quite apart from the fact that his grave is so far from his home on the other side of the world. There is the statement, inscribed on the grave surround, that Allan was the only son of Horace and Floradora – known as Dora to her family.

Lieutenant

Allan Isaac Davey Image credit: Virtual

War Memorial Australia

In other details I was helped by

Mairi Rowan in Australia, who manages the Davey family genealogical site. Mairi

told me that Allan had been named after his uncle, Lieutenant Allan Isaac Davey

(1889-1917), a schoolteacher who had enlisted for WW1 in 1915 with the 32nd

Infantry Battalion. He was killed two years later at Passchendaele, in

Flanders, Belgium, on 22 October 1917. I noticed the ironic similarity of his

age, 22 years old, the same age at which his nephew Allan Edward Dearlove would

die in WW2. Even the date of Allan Isaac’s death seemed significant.

In fact WW1 had been brutal for the Davey family. Allan Edward Dearlove’s father, Horace Edward Dearlove Davey, had been severely wounded in the right arm and leg. His brother Allan Isaac Davey had been killed in the same month. A cousin, Arthur Davey, serving in the 50th Battalion, had been killed in action in France, also in 1917. Another cousin, William Davey, had been wounded just after the war, in 1919.

The Terowie Institute, dating from 1879, one of

a number of authentic and well preserved 1880s buildings in this South

Australia town Image credit:

Peterdownunder/Wikipedia

The English origins of the Davey family were in Essex. Isaac Davey (1828-1914) born in the village of Rivenhall had arrived in Australia with his wife Eliza (1829-1917) born at Witham. Their son, Edward C. Davey (1860-1900) married Caroline Susan née Dearlove (1865-1956) but tragically died in Broken Hill Hospital aged only 40, possibly as the result of a mining accident.

Their four sons included Allan’s father, Horace Edward Dearlove Davey (1887-1978), born in the small town of Terowie in South Australia, 220 kilometres north of the state capital of Adelaide, and declared a ‘historic town’ because of the number of authentic and well preserved 1880s buildings. By the time of Allan’s birth on 12 August 1921 the family had moved to Unley Park, an affluent inner southern suburb of Adelaide.

Later, they would move to Fullarton, another Adelaide district, as noted on the grave in St Peter’s Burial Ground.

No. 4 Service Flying Training School (4 SFTS). Course No. 22, A Squadron, Flight 10. The photo was taken in about January 1942. Allan is circled in red. Image credit: Australian War Memorial

On 8 November 1941, 20-year-old Allan enlisted at Adelaide in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) with the Service Number 416939.

In 1939, just after the outbreak

of WW2, Australia had joined the Empire Air Training Scheme, under which flight

crews received basic training in Australia before travelling to Canada for

advanced training.

Recruits started their training at an Initial Training School (ITS) to learn the basics of Air Force life. The course ran 14 weeks for prospective pilots, 12 weeks for air observers, and 8 weeks for air gunners. No. 4 ITS was at Victor Harbor, South Australia, about 80 kilometres (50 miles) south of Adelaide.

I have not discovered whether Allan went on for further training in Canada, but in due course he was posted to Britain where he joined the RAF’s 90 Squadron. A total of 17 RAAF bomber, fighter, reconnaissance and other squadrons served initially in Britain and with the Desert Air Force located in North Africa and the Mediterranean. About nine percent of the personnel who served under British RAF commands in Europe and the Mediterranean were RAAF personnel.

In the European theatre of the war, RAAF personnel were especially notable in RAF Bomber Command: although they represented just two percent of all Australian enlistments during the war, they accounted for almost twenty percent of those killed in action.

No. 90 Squadron started life as a fighter squadron of the Royal Flying Corps in 1917 during WW1 but was reformed as a light bomber squadron in March 1937. After a period as a training unit in the early stages of WW2 it was reformed once more at RAF Watton, Norfolk, on 7 May 1941 as Bomber Command's only unit equipped with the American Boeing Fortress I four-engined heavy bomber. It moved yet again on 15 May to RAF West Raynham, still in Norfolk.

A B17 Flying Fortress performing in 2014 at the Chino Airshow Image credit: Airwolfhound

Difficulties were experienced with the Fortress I. In 51 operational sorties, 25 were abandoned due to faults with the aircraft, with 50 tons of bombs being dropped, of which only about 1 ton hit the intended targets.

Aircrew in full flying kit in the Spring of 1942 walking beneath the nose of Short Stirling Mark I, N3676 'S', of 1651 Heavy Conversion Unit at Waterbeach, Cambridgeshire while the ground crew run up the engines. The pilot (2nd from left) has been identified as an American, Sergeant Leonard A Johnson. Also believed to be shown are Sergeant Rennie, engineer (far right), Sergeant Jock McGown, rear gunner (2nd from right), Sergeant Agg (3rd from right), Sergeant Lofthouse (4th from right) and Sergeant J King, navigator (left).

Image credit: Charles E. Brown - Photograph TR 9

from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

On 7 November 1942 the Squadron again reformed as a night bomber squadron, part of No. 3 (Bomber) Group, at RAF Bottesford, on the Leicestershire-Lincolnshire border. It was to be equipped with the Short Stirling Mk.I, receiving its first Stirling on 1 December and moving, yet again, this time to RAF Ridgewell in Essex on 29 December 1942. Its first operational venture consisted of mining sorties on 8 January 1943.

The pilots' instrument panel and flight

controls of a Short Stirling Mk I of No. 7 Squadron RAF at Oakington,

Cambridgeshire. Image credit: Pilot Officer W. Bellamy, Royal Air Force

official photographer - Photograph CH 17086 from the collections of the

Imperial War Museums

The months following saw the Stirling Mk.III - an improved version - introduced to the Squadron, which moved to RAF Wratting Common in Essex on 31 May 1943. The unit's resources were thrown into the Battle of the Ruhr and sent to many of the German targets that were most heavily defended, including Berlin. The Squadron suffered considerable losses over an eight-month period and found it difficult to maintain reserves of men and machines.

Perhaps because of the shortage of personnel Allan gained much experience in a short time and was rapidly promoted to Flight Sergeant. There is an interesting comment on the No.90 Squadron RAF Facebook site to the effect that not all aircrews had an officer, and that was certainly the case on Allan’s last flight, when he was the pilot. You can find the site here

The wedding of Allan and Doris at St Peter’s Church in Budleigh Salterton

L-r:

Frank Sedgemore, Allan and Doris, Mary Sedgemore

Somehow, despite all these moves around airfields, Allan met Doris Sedgemore and the wedding took place at St Peter’s Church in Budleigh. Two years younger than Allan, Doris Lilian Marjorie Sedgemore was the youngest of nine children born to Tom Sedgemore and his wife Gertrude Mary née West. Sedgemore is a frequently encountered family name in Budleigh’s history: I counted 15 Sedgemores in parish records, seven of them with graves in St Peter’s Burial Ground, including Doris’ parents.

Tom himself was born in the town in 1886 and died in Budleigh on 27 April 1964, aged 77. His wife died there on 1 August 1967, aged 85 according to parish records.

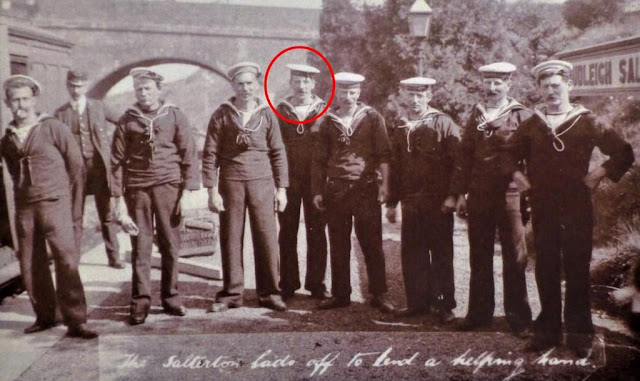

Caption: The Salterton lads off to lend a helping hand.

L-r: Walter Mears, Harry Rogers, William Sedgemore, Tom Sedgemore, Charlie Pearcey, Frank Mears, Jack Pearcey, and William Pearcey

Doris' father, Tom Sedgemore, can be seen in

this WW1 picture taken on 4 August 1914 by well known local photographer Frederick

Thomas Blackburn. A copy was used for the Great War exhibition at Fairlynch

Museum in 2014.

Tuddenham St Mary village sign. Little remains of the RAF station, but it is remembered on this sign. Image credit: Uksignpix

The RAF Tuddenham Memorial, with the village War Memorial in the background. Image credit: Adrian S Pye

A further move to RAF Tuddenham, near Mildenhall in Suffolk, came for Allan and 90 Squadron on 13 October 1943, still flying the Mark III improved Short Stirling aircraft. Designed by Short Brothers of Belfast in the 1930s, the Short Stirling was the first four-engined bomber to be introduced into service with the Royal Air Force.

Stirling N3663/MG-H of No 7 Squadron, on display

at Newmarket Heath, Suffolk, during a visit by King Peter of Yugoslavia, 29

July 1941. A typical bomb load is on view beneath the aircraft for the King's

inspection Image credit: Imperial War Museums

Beginning

in spring 1942, they began to be used in greater numbers, and by May 1943, air

raids over Germany involving over 100 Stirling bombers at once were being conducted. It was armed

with three pairs of 7.7mm Browning machine guns at the nose, side and tail and

carried 6,803kg (15,000lb)

of bombs internally.

A flight of No 1651 Heavy Conversion Unit

Short Stirling aircraft flying south-west, with the outskirts of Waterbeach in

the foreground and Cambridge in the distance. From near to far the aircraft

are: `S' N3676; `G' N6096; `C' N6069.

Image credit: Imperial War Museums

During its use as a bomber, pilots praised the type

for its ability to out-turn enemy night fighters and its favourable handling

characteristics whereas the altitude ceiling was often a subject of criticism.

The Short Stirling had a relatively brief operational career as a bomber before

being relegated to second line duties from late 1943. This was due to the

increasing availability of the more capable Handley Page Halifax and Avro

Lancaster, which took over the strategic bombing of Germany.

During its later service, the Short Stirling was used for mining German ports. From the start of WW2, Britain and Germany made significant use of aerial minelaying, with mines dropped by parachute in bays and sea lanes.

The

missions were known colloquially as ‘gardening’, with code names given to areas

in which the mines were dropped. Some people thought of them as an easy option

or ‘a piece of cake’ as RAF veteran Arthur Adams recalled from the comments made by fellow-airmen as he

set off on a mine-laying mission. His account of being shot down and captured by an enemy ship in the Bay of

Biscay and his time as a PoW has been published online by his family and is

well worth reading here

It's true that in some ways a ‘gardening’ mission was a relief from flying through the dazzle of searchlights and hail of murderous flak over the heavily defended cities of enemy territory. But low flying over water at night, often in virtually no moonlight, was no ‘piece of cake’.

The missions were usually undertaken by one single aircraft, giving the crew an uneasy sense of isolation. Cloud would often prevent them from checking to see that the parachutes had opened. It was essential for the pilot to steer an accurate and steady course, while the navigator and bomb-aimer had to have a high level of concentration to ‘sow’ the mines in the correct location. Needless to say, all members of the crew had to be on full alert for spotting coastal flak, ship-mounted artillery and the odd enemy night-fighter. Tiredness could have fatal consequences.

The Bomber Command Research Group, on its Facebook page, quotes from a Bomber Command Report of 1941. ‘It is not unusual for the mine-laying aircraft to fly round and round for a considerable time in order to make quite sure that the mine is laid exactly in the correct place. It calls for great skill and resolution. Moreover, the crew does not have the satisfaction of seeing even the partial results of their work. There is no coloured explosion, no burgeoning of fire to report on their return home. At best all they see is a splash on the surface of a darkened and inhospitable sea.’

The RAF's postwar analysis of Bomber Command's efforts, had this to say: ‘The main contribution which the strategic air forces made in the conduct of sea warfare was in the minelaying campaign. During the war Bomber Command laid 47,000 mines, which were responsible for sinking or damaging over 900 enemy ships. The Command was in fact responsible for over 30% of sinkings inflicted on enemy merchant shipping in northwestern waters.’

You can find the Bomber Command Research Group here

The Frisian Islands Image credit: www.626-squadron.co.uk

It was following a mining mission that Allan’s

aircraft crashed, killing him and four other members of the seven-man crew. Stirling

EF198 took off from RAF Tuddenham at 7.55 pm on Friday 25 February 1944, with

Allan as the pilot, heading for the Frisian Islands – codenamed ‘Nectarines’ – in

the Baltic Sea. It was probably carrying its full payload of six mines.

The distance to ‘Nectarines’ is about 270 miles. The Stirling Mark III had a maximum speed of 270 mph, reduced to about 165 mph with a full load.

Having reached the target area it would have to descend to 200 feet to drop the mines and then climb back to full altitude.

It may have spent some time circling the area before setting out on the homeward journey. What we do know is that while descending through cloud the aircraft struck some trees on a 250 foot hill and crashed at 2.55 am at Denham Castle, six miles south-west of Bury St Edmunds. Two crew members Sergeant E B Roberts RAFVR (Mid Upper Gunner) and Sergeant F W Tasker RAFVR (Rear Gunner) were injured.

Image credit: https://trove.nla.gov.au

This report was published in an Adelaide newspaper under the heading Private Casualty Advices: ‘Mr. and Mrs. H. E. D. Davey, of Fisher street, Fullarton, have been advised that their only son, Flt Sgt. Allan Edward Dearlove Davey, lost his life in an air crash in England on February 26. He was the pilot of a Stirling aircraft detailed to carry out mine laying operations when he crashed near Denham Castle, Suffolk, four miles west of North-West Chedburg. A private funeral took place at Budleigh Salterton. South Devon, on March 1.’

In a report that he made later Sergeant Roberts stated: ‘He heard on the radio the Pilot given landing instructions of Turn 4, QFE [a code used to refer to atmospheric pressure and altimeter readings] and height of cloud base. The Pilot then informed the crew he was going to break cloud and circle below 350 feet. The aircraft was descending and the Mid Upper Gunner felt a violent change in altitude of the aircraft as though the Pilot had pulled the control column hard back, and then the crash had occurred.’

Despite his injuries Sergeant Roberts went to the aid of Sergeant Tasker who was in his turret with both his legs broken.

Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, Hackney, London in 2005. It

is known as one of the 'Magnificent Seven' garden cemeteries of London Image credit: Fin Fahey

In addition to Allan, four crew

members were killed. One was Flight Sergeant John David Eaton RAFVR (Wireless

Operator), who was buried at Abney Park Cemetery in his home area of Stoke

Newington, London.

The grave of Edward Lionel Parrish in St Mary the Virgin churchyard, Lydney Image credit: www.findagrave.com

Sergeant Edward Lionel Parrish RAFVR (Flight Engineer) was buried in his home village of Lydney in Gloucestershire.

Brookwood Military Cemetery Image credit: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Also killed were two Canadians: Warrant

Officer II Joseph Jean Paul Adrien Rodrigue RCAF (Air Bomber), from Montreal, and

Warrant Officer II George Edward Stringer RCAF (Navigator), from Toronto. They were

buried at Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey.

A military grave for Allan in St Peter’s Burial Ground, Budleigh. Image credit: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The next post is for PRIVATE REGINALD LEONARD CRITCHARD (1921-44)

who died on 29 April 1944 in Burma while serving in the 1st Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment. You can read about him at

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2021/03/ww2-75-29-april-1944-casualty-of-kohima.html

Comments

Post a Comment