WW2 100 – 16 July 1944 – A leader ‘full of dash and courage’: Major George Tristram Palmer (1915-44) 12th Airborne Battalion, Devonshire Regiment

Continued from 9 July 1944

AIR MECHANIC (L) 2nd CLASS ALFRED EDWIN CLARKE (1910-44) Royal Navy, HMS Ukussa

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2021/03/ww2-75-9-july-1944-death-on-island.html

Budleigh Salterton War Memorial at the junction of

Coastguard Road and Salting Hill

It’s frustrating to find no obvious local connections with

a name on a war memorial. With George Palmer it’s the opposite: the Palmer name

is well known in Budleigh Salterton and the surrounding area. George himself is

remembered by at least one local person as a heroic figure who died ‘parachuting

into Arnhem’. In reality he died well before Arnhem and is buried in Normandy.

It is worth pointing out, incidentally, that George’s name appears on the otherwise excellent Devon Heritage website as C.T. Palmer, his death being ‘Not yet confirmed’. It’s clearly an understandable misreading of the inscription on Budleigh’s War Memorial.

As this WW2 project progressed, and probably because it's based on a chronological approach, I found that the individual profiles I was writing were getting longer and longer. After all, I was aiming to cover the family background of individuals as well as their wartime service, and not just the immediate circumstances of their death.

In some cases, especially when I’ve been in contact with an individual’s family, papers from the past – anything from 1930s’ school reports to letters of condolence from a commanding officer – have suddenly arrived on my desk, and I found that I was writing a biography rather than a simple tribute.

In George’s case, it was an envelope full of original papers which came to me at a late stage in my research, and which meant that I had to rewrite some of my text! But I felt honoured to be entrusted with such precious material that might help, in some strange way, to bring one of Budleigh’s war dead back to life.

Their names are all around us, and too often they might be forgotten. When I

first arrived in Budleigh I noticed the unusual name of the builder on this

manhole cover. A few years later, in 2014, I was involved with our local museum’s

centenary exhibition ‘The Great War at Fairlynch’. Finding that his son, Sidney

Alfred Demant, had been killed in Flanders in 1915 encouraged me to write a

little bit more than usual. You can read Sidney’s profile here

The Palmer name on Budleigh’s pavements

As

far as I know, there is only one Alfred Demant manhole cover in Budleigh, but

you can see many bearing the Palmer name.

And looking up, you can see more evidence of the Palmer family’s importance in the town.

Local resident Jim Gooding, among his memories recorded in the 1987 Devon Books publication Budleigh Salterton in Bygone Days, recalled that the firm Palmer’s employed some 200 people in various projects: ‘You name it, Palmer’s would do it for you, big or small, from furnishing a complete house to acting as funeral directors.’ Palmers Estate Agents eventually merged with the firm of Whitton & Laing.

Budleigh people still remember the sound of Palmer’s bell. Jim Gooding explained: ‘At the beginning of the working day numbers of workmen would be seen at the entrance to the passage in High Street waiting for the large bell to ring calling them to work, much the same as a factory hooter would do. This bell, known to all as Palmer’s bell, could be heard at long distances and was generally accepted as correct time, as indeed it was. It was used as timekeeper for a lot of other workers of the firm, in whatever part of the town they were working.’

Budleigh artist and author Joyce Dennys is thinking of it when she writes of ‘Barton’s Bell’ in an amusing episode of her Henrietta’s War. The book is set in a small Devon coastal town which is clearly Budleigh Salterton: ‘Its sonorous and mellow tones were very dear to us all, and when they stopped ringing it at the beginning of the war our lives immediately became horribly disorganized. Nobody ever knows quite what the time is now, and a lot of people, who had managed quite comfortably up till then, have been forced to buy watches.’

Image credit: Paul Kurowski and The Imperial War Museums

The Palmer name also appears on All Saints’ Church memorial in East Budleigh, as seen above, and on the village War Memorial, the family having been associated with East Budleigh for generations. George’s grandfather, John Copplestone Palmer (1853-1922) was born there, the son of John Palmer (1820-88) and his wife Eliza née Priddle (1814-1901). In a Kelly’s Directory of approximately 1890 which lists East Budleigh residents, John Copplestone Palmer is shown as ‘draper, builder & undertaker, assessor of taxes, assistant overseer & clerk to Parish Council, Post office’. Evidently a man with his finger in many pies.

You can see from this photo of East Budleigh War Memorial that George’s death in 1944

was the second of two Palmer family deaths to be recorded. His uncle, Sergeant Tristram

Copplestone Palmer, had been

wounded in action on 30 August 1918 and died of his injuries in hospital the

same day.

George was one of four children born to John William Palmer and his wife Ellen née Thorne. His elder brother, John Copplestone Palmer is listed as being born in 1913 at 1 Victoria Place in Budleigh Salterton. George was born two years later, on 18 July 1915, apparently in East Budleigh.

Their father served in WW1 as a Captain in the 9th Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment but managed to survive. When Budleigh’s War Memorial was unveiled on 11 November 1922, four years to the day after the Armistice, it was John William Palmer who led the parade to mark the occasion.

In the 1930s, John William Palmer was listed in Kelly’s Directory as a house and estate agent at 47 High Street in Budleigh. But his interests extended beyond the town.From research by Otterton archivist Gerald Millington we learn that in 1929 he was described as a builder of Budleigh Salterton, leasing ‘all the beach and foreshore, down to low watermark, of sea at Ladram Bay’, which does suggest that a field had been set aside earlier for a camp site. In March 1932, he was leasing for 99 years, three fields behind the old cottage and erecting a tea house. When WW2 broke out, the Army Authorities requisitioned the camping site and beach and paid him a token rent.

George grew up locally. At some stage the family moved to a new home, The Lawn, a large house with a garden which extended on to Station Road.

This must be him in the photo seen above of the 1926-27 St Peter’s

School football team, part of a display at Fairlynch Museum. He looks about the

right age.

I wondered whether, after St Peter’s School, George had attended The King’s School, Ottery St Mary, as his uncle Tristram Copplestone Palmer had done. But among the family papers that I was sent I found reports from Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School in Crediton. They are dated from 1930 to 1932, and make interesting reading.

A postcard of the old Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School, Crediton

Schools in Ottery, Exmouth and even Exeter would have been a lot closer to

Budleigh Salterton than Crediton, but Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar School had an

excellent reputation.

Known today simply as Queen Elizabeth’s School, its origins go back to when it was founded as ‘The Kyng's Newe Gramer Scole of Credyton’ in 1547 by King Edward VI and re-endowed and renamed in 1559 by Queen Elizabeth I.

By the mid-19th century, according to the website of its modern

incarnation, it was known as ‘the best grammar school in Devon.....equal to even the more famous and

well endowed public schools such as Blundells’. And it had a boarding section as

I learnt from the school reports.

Image credit: www.militaryintelligencemuseum.org

I noticed that among

its former pupils was Major Rupert Guy Turrall DSO, MC, pictured above, a WW1 war hero born in

Great Torrington, Devon, in 1893.

Known as a highly eccentric character, he has been identified as a likely model for Captain Apthorpe in Evelyn Waugh’s 'Sword of Honour' trilogy. In 1939 he was commissioned into the Intelligence Corps and was awarded the Military Cross for his service with the Sudan Frontier Force in Abyssinia. He was then recruited by Special Operations Executive (SOE) Force 133, serving in Crete, before transferring in 1944 to the Chindits in Burma. In September of that year he joined SOE Force 936, his achievements including a highly successful attack on the Japanese Kenpeitai headquarters at Kyaukkyi.

Could such a lively

character have inspired George, I wondered? But Turrall had been one of Queen Elizabeth’s Grammar

School’s academically gifted pupils. After the war he completed his degree in geology and

astronomy at Cambridge, and worked as a geophysicist.

Rupert Turrall would probably have been encouraged by the Grammar School’s

Headmaster of the time, Frank Clarke. A scholar at Emmanuel College, Cambridge,

Clarke is listed as the University’s 11th highest-scoring

mathematician of the year – an 11th Wrangler as it is known – when

he graduated in 1902. He went on to be an Assistant Master at Mill Hill, London

and Headmaster at Bromsgrove, Worcestershire – both respected public schools –before

being appointed to the Headmaster’s post at Crediton in 1912.

George's 1930 school report: Oh dear! 22 out of 24 for his form position

Judging by his school reports, George clearly did not match that kind of academic success. His first report from Headmaster Frank Clarke was not enthusiastic: ‘Much too easily satisfied with his achievements. Must tackle his difficulties & not avoid them.’ He was, observed Mr Clarke in later reports, ‘a very nice boy in many ways but noisy & still much wanting polish.’ And ominously, ‘He should also make a wiser choice of companions’ and has ‘more energy than discretion’.

The Form Master's 1932 verdict: 'Noisy', noting George's 'natural boisterousness'

As for the Headmaster’s favourite subjects, throughout his time at Queen Elizabeth’s, George found Maths and the Sciences difficult. ‘Weak’, 'examinations really poor', ‘He might at least try to work neatly’ and ‘He does not shine in the subject’ were typical teachers’ comments. I sympathised!

By contrast he was praised for his work in Geography and History, and seemed keen and motivated as a piano player.

His ‘superabundant energy’ and attractive qualities were recognised by most teachers. As far as physical exercise was concerned he was impressive throughout his time at school – apart from an odd comment in the final term: ‘Makes very little effort’.

A 'satisfactory' end to George's time at Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School in 1932

But generally he had benefited from his years at Queen Elizabeth’s, and the Headmaster’s concluding verdict in the final year – though somewhat brief – was ‘A satisfactory term’.

Exeter Chiefs logo Image credit: Wikipedia

George

was notable for his enjoyment of sport, and especially rugby. He is commemorated in a World War Remembrance section on

the Exeter Chiefs website, where he is described as a native of East Budleigh.

He first appeared in Exeter colours during the 1931-2

season, while still at school, and from 1933-34 until the outbreak of war he was a regular selection,

as featured in the above photo, kindly supplied by Kevin Curran. His fellow-players

remembered him as ‘a second-row forward who revelled in the hardest work’. He was also a keen cricketer and a member of Budleigh Salterton Cricket Club.

Cap badge of the Devonshire Regiment Image credit: Wikipedia

George

would have been aware of the military tradition in his family, for we find him in the

pre-WW2 years as a member of what had become known as the Territorial Army (TA)

from 7 February 1920. Previously it had been the Territorial Force (TF).

His commission as a 2nd Lieutenant with the 4th Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment from 19 May 1934 was announced in the London Gazette of the previous day, and he was promoted to Lieutenant on 19 May three years later.

George was certainly an enthusiastic soldier even

if part-time. An obituary in the 'Aylesbeare Magazine' of

August 1944 notes that he was a Territorial Army officer for ten years.

A poster for the film O.H.M.S. with its American title

Image credit: www.alchetron.com

Among the family papers that I read was an undated letter from him to his parents. It is addressed from 267 Camden Road, N7, and suggests that he may have been engaged in TA activities while working in London in the 1930s. ‘I’ve been doing a bit of bayonet fighting,’ he tells them. ‘It’s very good fun, but it does make you hot – you have to wear so much.’

He concludes by recommending

that they go to see ‘O.H.M.S’ if it comes to Exmouth – ‘it’s a very good film

indeed,’ he writes, suggesting that the letter would have been written in 1937

when this British adventure film was released. Given the title ‘You’re In The

Army Now’, it starred Wallace Ford, John Mills, Anna Lee and Grace Bradley, and

concerns an American gangster who flees to England, joins the British Army and

finds romance and adventure on campaign in China!

From wonderful Wikipedia I learnt the following about the film: ‘Seeking to use cinema to counter the anti-militarist and pacifistic public atmosphere that predominated in the late 1930s in England, and foster an Anglo-American spirit on either side of the Atlantic Ocean in the prelude to the outbreak of World War II, the Gaumont British Picture Corporation engaged the American Director Raoul Walsh, and the Anglo-American star Wallace Ford to produce a film showing life in the British Army in an entertaining and positive light, in the same manner that Walsh had done for the United States Marines Corps in ‘What Price Glory?’

After the Munich Crisis in late 1938 the TA was doubled in size, and once again its units formed duplicates. The 4th Battalion's duplicate was the 8th Battalion (taking the number of the regiment's first 'Kitchener's Army' battalion in World War I), which was formed on 25 May 1939 at Yelverton, near Plymouth.

The divisional insignia,

Drake's Drum, denoting the association of the Division with the West Country

region. Image credit: Imperial War Museums/Wikipedia

Before WW2 was declared he was mobilised on 24 August 1939. On 7 September the 4th, 6th and 8th Battalions of the Devonshire Regiment were serving in the 134th Brigade, which came under control of the 45th (Wessex) Division. Formed that year from the 4th Battalion, the 8th was mobilised at Exmouth under the command of Lieutenant Gavin Young. The Phoney War period, for the months from September 1939 to April 1940, was spent training in the Regiment’s West Country home area, including at Yelverton, under Southern Command.

It was during his time at a camp near Yelverton that Budleigh resident Prilli Stevens remembers making the acquaintance of George. He became ‘a marvellous friend’ to her family, persuading them to move away from Plymouth to the safety of Budleigh, where his parents found them a house.

Among the family papers that I read was another undated letter from George which gave as his address: 8th Battalion, Devonshire Regiment, Cherry Tree Camp, Colchester. It seems to confirm that he moved from the earlier 4th Battalion.

I do not have access to George’s service record, but am indebted to Facebook’s The Devonshire Regiment WW2 LHA, a page which is run by WW2 researcher Tony Crofts and other civilians, who, as they state, ‘have a desire to keep the memories of this once proud Regiment alive and uniting families together’. There, we learn that the 8th Battalion, after Yelverton, moved to the South-East coast with the rest of the 45th division. Further moves came: in May 1940, to Rossington, Yorkshire; in 1941 to Wokingham, Berkshire; in 1942 to Southminster, Essex.

Members of the Home Guard watch over Budleigh beach. Image credit: Rose Wakefield, from a wartime magazine

Meanwhile, George’s father was also playing his

part in defending Britain, perhaps with encouragement from his son. The same

undated latter written from Cherry Tree Camp, Colchester, asks: ‘Have you taken

over command of the H.G., Dad? I’m sure you would do B.S. a lot of good if you

did...’ Humorously, George adds ‘...

also be a bit unpopular with some.’

Perhaps he is thinking of the large number of retired senior military officers living locally who would have outranked his father and for which Budleigh was famous. The novelist R.F. Delderfield referred to the town as ‘Valhalla’ – the hall of slain heroes in Norse mythology.

In any event, promoted from Captain to Major, John William Palmer did indeed command the Budleigh Salterton and District Company of the Home Guard during WW2.

George is listed in military records as being promoted to Captain on 22 August 1942 and to Temporary Major on 9 February of the following year.

British troops charge with fixed bayonets through 'artillery fire' as part of their training in 1943. Image credit: Imperial War Museums © IWM H 34907

He was probably keen to be involved in a more active role rather than in coastal defence duties in the UK. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) lists him as a member not of the 8th Battalion but of the 12th Airborne Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment. He would have become part of an elite fighting force which had been conceived as a vital element of the planned Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Europe.

Impressed by the success of German airborne operations during the Battle of France, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill directed the War Office to investigate the possibility of creating a force of 5,000 parachute troops. As a result, on 22 June 1940, No. 2 Commando assumed parachute duties, and on 21 November was re-designated the 11th Special Air Service Battalion, with a parachute and glider wing. This later became the 1st Parachute Battalion, part of the 1st Airborne Division.

On 31 May 1941, a joint Army and RAF memorandum was approved by the Chiefs-of-Staff and Churchill; it recommended that the British airborne forces should consist of two parachute brigades, one based in England and the other in the Middle East, and that a glider force of 10,000 men should be created.

Two years later, on 23 April 1943, the War Office gave permission to raise a second airborne division, the 6th Airborne. The division comprised the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades and the 6th Airlanding Brigade, the latter to be part of the projected glider force.

The experienced battalions which made up the Brigade were joined by men newly transferred to the airborne forces, from the 12th Battalion of the Devonshire Regiment, otherwise known as the 12th Devons. Specially selected for their resilience and fighting qualities, these were the troops who made up the Devonshire Regiment’s 12th Airborne Battalion.

Budleigh

beach in wartime Image credit: Rose Wakefield,

from a wartime magazine

Early

in the war, the 12th Battalion had manned the defences on the coast

near Dawlish, moving in December 1940 to Budleigh Salterton. In the late

summer of 1942 they moved from the Exeter area to join 214th Brigade on the Isle of Wight, where they

remained until they moved to Truro in May 1943. A few weeks later the 12th

Devons were suddenly ordered to Bulford Camp on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire to

become a glider-borne battalion and part of the 6th Airborne Division.

Airborne troops seated in an Airspeed Horsa of

the Heavy Glider Conversion Unit at Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, ready for take

off. Image credit: Imperial War Museums

From June to December 1943, the 6th Airlanding Brigade, as part of the 6th Airborne Division, prepared for operations, and trained at every level from section up to division by day and night. Airborne soldiers were expected to fight against superior numbers of the enemy equipped with artillery and tanks. So training was designed to encourage a spirit of self-discipline, self-reliance and aggressiveness. Emphasis was given to physical fitness, marksmanship and fieldcraft.

A large part of the training consisted of assault courses and route marching. Military exercises included capturing and holding airborne bridgeheads, road or rail bridges and coastal fortifications. At the end of most exercises, the troops would march back to their barracks, usually a distance of around 20 miles (32 km). An ability to cover long distances at speed was expected: airborne platoons were required to cover a distance of 50 miles (80 km) in 24 hours, and battalions 32 miles (51 km).

Artist Albert Richards’ (1919–1945) painting ‘Exercise “Mush”: Gliders Land on a “Captured” Airfield and Paratroops Surround the Field, Waiting for the Unloading of the Gliders’.

Image credit: Imperial War Museums

In April 1944, under the command of I Airborne Corps, the brigade took part in Exercise Mush. This was a three-day exercise in the counties of Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire and Wiltshire, during which the entire 6th Airborne Division was landed by air. Unknown to the troops involved, the exercise was a full-scale rehearsal for the division's involvement in the imminent Allied invasion of Normandy.

Landing ships putting cargo ashore on

Omaha Beach, at low tide during the first days of the operation, mid-June 1944. Image credit: Wikipedia

Airspeed Horsa gliders on Landing Zone 'N', 7 June 1944. Image credit: Flt Lt Kelly : No. 106 (PR) Group. - This is photograph HU 92976 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

Operation Overlord was launched on 6 June 1944 with the Normandy landings. A 1,200-plane airborne assault preceded an amphibious assault involving more than 5,000 vessels. Nearly 160,000 troops crossed the English Channel on 6 June, and more than two million Allied troops were in France by the end of August.

The Operation was a massive undertaking, and dramatic in its impact on the course of WW2. It’s no surprise to find hundreds – if not thousands – of online sites where there is useful information helping to piece together our understanding of what D-Day and the invasion of Europe meant for those who experienced it. WW2 researcher and historian Mark Hickman, like Tony Crofts, has devoted much energy to gathering material about British airborne forces in the period 1940 to 1945 on his website here

I do not know whether George took part in operations like Exercise Mush. Neither Mark Hickman nor Tony Crofts could find any mention of him in Devonshire Regiment records for this period.

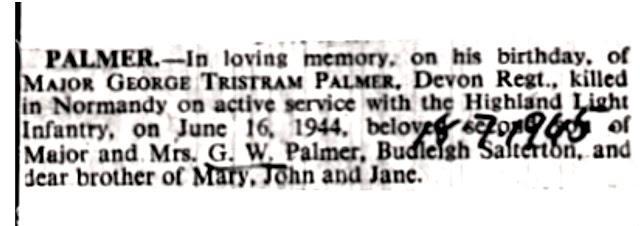

A puzzle solved! This memorial notice from the Exmouth Journal newspaper mentions the Highland Light Infantry

After a day or so of fruitless web searches the

puzzle was solved when my friend Carolyn John came across memorial notices

published in local newspapers in the years after George’s death. At some stage in

early 1944 he moved from the 12th Devons to 33 RHU, one of a number

of Reinforcement Holding Units. From there, he was seconded to the Highland

Light Infantry (HLI), a Territorial unit.

I can imagine that in the turmoil of preparations for the invasion there was a fair bit of shuffling of personnel. Along with George, two newcomers to the 10th Battalion who would be killed in action at around this time were Canadian officers Lieutenants Albert R. Harding and David G. Hilborn.

1st Battalion The Highland Light Infantry

marching down Military Hill, Dover, 1931 Image credit: National Army Museum

For George, a Devonian with no Scottish ancestry as

far as I know, his new unit with its special traditions would have been a very

different experience. Formed in 1881, the HLI drew its recruits mainly from

Glasgow and the Scottish Lowlands.

In 1923, the Regiment's title was expanded to the Highland Light Infantry (City of Glasgow Regiment). One of its well known members was David Niven, who was commissioned into the Regiment in 1930 and served with the 2nd Battalion.

As a duplicate of the 5th Battalion when the Territorial Army was doubled, the 10th Battalion was formed at Maryhill Barracks, Glasgow in 1939. The 6th and 9th HLI formed duplicate 10th,11th and 2/9th Battalions.

Left: The front cover of the history of the 10th HLI, European Campaign, 1944-45 as recorded by Captains R.T. Stewart, D.N.

Steward and Rev I. Dunlop, Chaplain, with a Dedication and Foreword, originally

published in 1950. Right: A new 78-page softback edition has been published by

the Naval & Military Press

From February to May 1941, the Battalion was on defence duties in the East of England at Danbury and Ipswich before moving to the Shetlands in 1942. In the following year it was at Loch Watten in Caithness, Northumberland and Sledmere, Yorkshire, before forming up in preparation for D-Day in 1944. The 10th HLI was part of the 46th Infantry Brigade, and from 3 December 1942, the 227th Infantry Brigade. Both were part of the 15th Scottish Division.

Cap badge of the Highland Light Infantry. The elephant is probably a reference to the Regiment's action at the 1803 Battle of Assaye in India Image credit: Wikipedia

George and its 10th Battalion did not arrive in France until after D-Day, and in fact he did not join the Battalion until a month later. Initially, I was at a loss to know exactly when. But I was keen to discover every detail of the military background in which he served, and this led me to find out more about the 10th HLI and discover what its experience of Operation Overlord had been.

We read in the Battalion’s war diary that advance parties of three officers and six other ranks set out for France on 9 and 11 June. The rest of the Battalion embarked in LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry) and set off for France in convoy at 6.00 pm on 17 June, arriving 8.00 am the next day at Courseulles-sur-Mer where they waded ashore. A hot meal was served by a Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) unit, and the following week seems to have been uneventful apart from the shooting down of a German Dornier 217 bomber in the late evening of 20 June. After that, it was a different story.

Two photos showing

men of the 10th Highland Light Infantry advancing during Operation 'Epsom', 26

June 1944. On the left in the top photo are two Sherman Crab flail tanks. Top

photo image credit: Sgt Laing No.

5 Army Film and Photo Section, Army Film and Photographic Unit. Imperial War

Museums. Lower photo image credit: www.wikiwand.com

Early on 26 June, units of the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division including the 10th HLI advanced behind a rolling artillery barrage in the British offensive Operation Epsom. Also known as the First Battle of the Odon, this was an attempt to outflank and seize the German-occupied city of Caen. Air cover was sporadic for much of the operation, because poor weather in England forced the last-minute cancellation of bomber support.

Reading the History of the 10th Battalion, it is clear that for most of the men Operation Epsom was a baptism of fire – ‘our first immediate experience of the din of battle’ – as the authors put it. Their account speaks of the smoke and stench of explosives mixed with bloated and burning carcases of cattle as the tank battles raged. Enemy snipers, hiding in the hedgerows and orchards and among the shattered remains of villages, are killed and in turn are themselves killed as the invasion force advanced steadily. And then retreat as mortar and artillery fire from the other side intensified.

Waffen-SS soldiers reload a German 81mm mortar.

Image credit: Wikipedia

Mortar fire caused an increasing number of deaths and injuries. German forces used mortars extensively and they allegedly accounted for 70% of British casualties in Normandy.

Topography of the area south-west of

Caen with my indications of military movements as found in my text. Image credit: Philg88/

Wikimedia Foundation

Day 1 of Operation Epsom saw the Battalion’s first casualties: one officer wounded; of the other ranks, one killed and eight wounded.

The Operation was resumed early the next day by the 10th Battalion, which had dug in at the village of Cheux. With support from Churchill tanks it was intended to make a bid for the River Odon crossing at Gavrus. The HLI immediately ran into stiff opposition from elements of the 12th SS Panzer Division and despite heavy artillery support were unable to advance all day. ‘That night we buried our first dead, saw many refugees tired and weary pass through the shattered streets, and dug-in once again round Cheux,’ reads the Battalion History.

Troops of the Scottish 15th Infantry Division in the village of St Mauvieu-Norrey in Normandy, during Operation 'Epsom', 26 June 1944. Image credit: Major Stewart, No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit. Photograph B 5968 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums

In mutually costly fighting over the following two days, a foothold was secured across the river and efforts were made to expand this, by capturing tactically valuable points and moving up the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division.

The Battalion experienced a determined German counter-attack on 29 June, being subjected to heavy mortar and shell fire which lasted all day. Many heroic actions are recorded in the Battalion’s History. 28-year-old HLI officer, Major Robert Buchanan Maclachlan, commanding ‘D’ Company, met his death, described by the authors in heroic terms: ‘fatally wounded, while personally leading an attack in the face of enemy tank cross-fire’.

Memorial on Hill 112 in Esquay-Notre-Dame,

Normandy. The inscription reads: ‘To the memory of all ranks of the 43rd

(Wessex) Division who laid down their lives in the cause of freedom June 1944

to May 1945. This memorial is erected on the site of the first major battle in

which the Division took part July 10th to July 29th 1944 when this ridge, château

de Fontaine, Éterville and Maltot were captured and held.’

In response to the German defense, the Battalion’s

own mortars came into action, aiming to capture the famous Hill 112, a high

point south-west of Caen described by the German General Paul Hausser as ‘the

key to the back door of the city’.

Otterton's twinning sign. Image credit: Kirby James

Hill 112 is close to the village of Vieux. When I

first moved to the Budleigh area I was intrigued to discover that this was the French

village twinned with the picture postcard village of Otterton with its ancient

thatched cottages. The two seemed so dissimilar, particularly in view of the

name, as Vieux seemed to consist mostly of modern buildings. Learning about the

bitter conflict of WW2’s Normandy campaign, with its terrible obliteration of so

many landmarks in ancient places, made me think.

By 30 June, after the German counter-attacks, some of the British forces across the river were withdrawn and the captured ground consolidated, bringing the operation to a close.

‘Our first week of fighting was over, and we were out to rest and refit,’ reads the Battalion History at the end of Operation Epsom. ‘We had learned much in a week. We had undergone that vital experience for all soldiers - the test under fire. And we had come out with colours flying and an enhanced reputation for our already famous regiment. Nor had it been without cost, for in that week we had lost 66 killed and 210 wounded.’

Fighting in the bocage landscape of Normandy with its hedgerows and sunken lanes must have been as difficult as in the jungle environment of Burma. Similarly, the fanaticism of Japanese soldiers in the Far East was matched by the ferocity with which extreme Nazis fought and in some cases for the cruelty with which they treated their prisoners of war.

Panzergrenadiers on a Panzer IV during training

1943. Image credit: Wikipedia

The 10th HLI had survived the first

week, and may well have been proud of their achievement in facing up to a

battle-hardened, determined and often fanatical enemy in the form of the 12th

SS Panzer Division ‘Hitlerjugend’, a German armoured division whose junior enlisted

men were drawn from members of the Hitler Youth. A post-war Investigation by

the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) Court of Inquiry into

war crimes committed by the Division determined that it ‘presented a consistent

pattern of brutality and ruthlessness’.

During the course of the Normandy Campaign an estimated 156 Canadian prisoners of war are believed to have been executed by the 12th SS Panzer Division in the days and weeks following the D-Day landings.

A smiling Nazi fanatic: Meyer’s sentence was

commuted to life imprisonment. He was released in 1954 and died in 1961. 15,000

people attended his funeral. Image credit: Wikipedia

The SS commander Kurt Meyer, who was sentenced to death after the war for his part in some of these crimes, is quoted as stating that he knew of at least three separate cases between 9 June 1944 and 7 July 1944 when one of his men tied explosives to his body and jumped onto an Allied tank to destroy it. Canadian historian Michael E. Sullivan sees such conduct as the acts of ‘teenagers who were systematically moulded into fanatical fighters by years of indoctrination by the Nazi leadership’. You can read his 2001 article ‘Combat Motivation and the Roots of Fanaticism: The 12th SS Panzer Division in Normandy’ here

The HLI History notes that the coolness and accuracy of the gun crews as they aimed at the approaching German Panzer tanks was ‘beyond praise’, and records acts of heroism by men such as a Captain Scott, who ‘without regard for his own personal safety, brought two of his anti-tank guns into action at a range of 100 yards and succeeded in knocking out all four tanks after a hard battle’.

But for many members of HLI there had been cruel news of the deaths of friends. Among the 66 was the Quartermaster, 54-year-old Glaswegian Captain Alexander Bain, killed on 28 June and regarded as ‘the father of the Battalion’.

A veteran of WW1, he was valued for ‘his experience, enthusiasm and unique personality’. The HLI History tells us that ‘the loss was most deeply felt by all ranks’.

At 3.00 am on Sunday 2 July the Battalion was relieved by the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Over the next few days it enjoyed a welcome period of rest in the village of Norrey-en-Bessin, apart from a short stay at St Mauvieu, mentioned in the HLI History.

There it was involved in reinforcing against a possible enemy counter-attack during Operation Windsor. This was an attempt by the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division between 4 and 5 July to capture Carpiquet and the adjacent airfield, from troops of the 12th SS-Panzer Division ‘HitlerJugend’.

For much of this period of early July there was a respite from the bloody conflict; for ten days between 3 and 13 July the summary of events in the Battalion’s official war diary is a relaxed-sounding ‘Situation normal’.

It was during this period, on 8 July, that George is recorded in the war diary as posted to the 10th HLI from 33 RHU (Reinforcement Holding Unit) to command ‘C’ Company.

Elsewhere in the Normandy Campaign, for other units, there was fierce fighting: Operation Charnwood, from 8 to 9 July, an Allied attempt to capture Caen. This was to prevent the transfer of German armoured units from the Anglo-Canadian front in the east to the American sector.

And from 10 to 11 July, Operation Jupiter, an offensive led by the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division to capture the villages to the west of Caen, including Baron-sur-Odon, and to recapture Hill 112 near the village of Vieux.

The church of Notre-Dame-des-Labours at Norrey-en-Bessin, as it is today. Image credit: Ikmo-ned/Wikipedia. The steeple was destroyed during the fighting in Normandy

However for the 10th HLI, ‘Situation normal’ continued. The History paints a charming picture of the Battalion’s stay in Norrey-en-Bessin, a village which ‘has pleasant memories for most’ – standing in sharp contrast with the rest of its time in Normandy. But, as the authors explain, ‘it was a rest and gave us our first contact with the French of whom the Duc will be best remembered’... leaving me to wonder whether their stay had included a lavish dinner at the Château.

Yet although the name Le Château is marked on the map, there is no building to match. Maybe, in an act of reprisal if the Germans had briefly re-taken the area, they later demolished it as punishment for Norrey’s welcome to the invading Allies. Who was the Duc, I wonder?

And on Friday 14 July, the Battalion shared in the village’s

celebrations to honour Norrey’s WW1 dead and two British soldiers who had been killed nearby. For the

procession it provided two pipers, a Padre and a detachment from its ‘A’ Company under

the command of Major Maurice Merrifield, recently joined from the Argyll and

Sutherland Highlanders Regiment, a brave officer who would be awarded the

Military Cross by Montgomery but sadly lose his life in Germany the following

year.

If George had attended the event it must have been very much part of a peaceful and civilised ‘interlude’ as the HLI History calls this midsummer period of rest for the Battalion.

Everything would change over the next few days. That very evening, the war diary tells us, the Battalion left for the area of Verson on the River Odon, arriving just before midnight and digging in. The Second Battle of the Odon was about to begin.

The 15th (Scottish) Division had been given the task of making a feint attack towards Evrecy to draw off the enemy’s armoured force while a major Allied offensive was launched at Caen. ‘C’ Company, led by George, set out as an advance party for Baron-sur-Odon on 15 June; the rest of the Battalion arrived there at 5.30 pm. Enemy shelling and mortaring lasted all night until 3.00 am next day.

A

Churchill tank fitted with a Crocodile flamethrower in action. This

flamethrower could produce a jet of flame exceeding 150 yards in length. Image

credit: Photograph TR 2313 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums

(collection no. 4905-03)

Meanwhile other units from the Division, with armoured support,

including Churchill Crocodile flame thrower tanks, attacked Evrecy and the high

ground on either side.

British infantry occupy slit trenches in the forward area between Hill 112 and Hill 113 in the Odon valley, 16 July 1944. Image credit: photograph B 7441 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums (collection no. 4700-29)

The 10th Battalion’s attack on Evrecy began at 5.30 am on Sunday 16 July but almost immediately its supporting tanks found themselves blocked by a minefield. Enemy observation from Hill 112 covered the entire area of the Battalion’s advance, and it was decided to consolidate in defensive positions south of Baron-sur-Odon.

Heavy fire was encountered, and many lives were lost, the death of George being described in the History as ‘the most grievous’. HLI researcher James Garven’s assessment of the situation is painfully realistic: ‘It seems that when the leading groups were held up the result was a congested battlefield of queueing units. German shelling and aircraft caused a large number of casualties.’

Among

the number of family papers that I was given were copies of three handwritten letters

from people connected with the Highland Light Infantry. The first was from

Lieutenant Colonel Ian Mackenzie, 2nd in Command, who was awarded a DSO

by Montgomery later in 1944 for ‘conduct beyond praise’:

Dear Mr Palmer

I trust that ere this you have been officially informed of the death of your son, and that this is not the first intimation you get. I am indeed very sorry to give you this sad news, and write to give you some details, which I know you must be anxiously awaiting.

When I joined this Bn - very recently as 2nd in command – your son was in command of ‘C’ Coy. I had little time in which to get to know him before we went into action. His Coy was in reserve, and the C.O entrusted him with the task of reconnoitering a route for tanks through our minefields. He did this, and marked it very well, and this greatly helped our operation. On completion of this task he assumed command of his Coy again.

Soon after daylight broke we were caught in very heavy mortar fire, and your son fell mortally wounded while getting his men under cover. We were in a ‘hot’ spot alright for some hours, and as the padre was not able to come up, I had the honour of burying him myself, in the presence of a few of his Coy. We buried him some three hundred yards south of the church in BARON between the rivers ODON and ORNE.

Being here only for a very short time I had little opportunity of getting to know your son, but I can say that the late Commanding Officer held him in very high regard, and that he was popular and well liked by his men. The C.O. was really distressed when he got this news.

May I add my deepest sympathy to you and all who were dear to him. I hope you will be comforted in the fact that he died gallantly for his country, and, we hope, for a better world to come.

Yours v. sincerely

Ian Mackenzie

A

second letter was from the Rev Ian A. Dunlop, Chaplain to the Highland Light Infantry,

who, after the war, would be one of the co-authors of the History of the 10th

Battalion:

Dear Mr Palmer

You will probably have

heard by now of the sad death in action of your son, Major G.T. Palmer. He was

killed in an attack on the enemy on 16th July, and had done very

well indeed, both on the previous night when the unit was under very heavy

shell-fire, and on the morning when he was killed.

He had not been with us for long, but we had grown to know him, and to respect his ability. We shall miss him here very greatly.

But the shock for us is as nothing compared to your loss. This must be a sad dark day for you. We can only pray that the cause in which he gave himself will be attained, and his sacrifice be not in vain. All our sympathies are with you.

I do not know whether Major Palmer was married or not. He gave you as his next of kin. But if he was, will you please convey to his wife my sympathy.

I am, believe me, yours very sincerely,

Ian Dunlop, Chaplain

Photos of the church of Baron sur Odon mentioned by Lieutenant Colonel Mackenzie and Captain Meecham in their letters, before and after restoration

Image credit: Dominique Bidart. You can see some of Dominique’s research into WW2 in Normandy here and here

Finally there was a letter addressed to Mrs Palmer by a Captain Meecham, who was serving in the 10th Battalion’s ‘C’ Company with George:

My dear Mrs Palmer

By this time you will have been officially informed that George has been killed in action in Normandy. I wanted to write you, firstly to tell you what happened, and secondly to express our very sincere sympathy in your loss. Although I had only known him for a week, during which time he was my Coy Commander I grew to like and respect him both as a man and as a soldier, and the officers and men in the Coy felt likewise.

He was killed on the morning of Sunday 16th July, and although I was a little way off from him at the time, I can vouch for the fact that he died ever so bravely. We were being shelled at the time, and he was wounded in the side, dying instantly. When I reached him the Padre was already there; there was nothing that we could do except say within ourselves, another fine chap has gone.

Please don’t be disturbed at me writing to you like this, but I know you would want to know, and besides George Palmer’s wife must be very brave. He spoke often of you & his home, he seemed to be very proud of you all, and you must be of him.

He is buried near where I am writing, just by a ruined French church, and like all the other graves which mark the ground which has been gained, there is a white cross there. His personal documents and papers have been collected by the Padre, who no doubt has already written to you.

If there is anything that you wish me to do, please write and ask, and I shall do my utmost to see that it is done.

May I close by saying how very sorry I am to tell you of his death, and how very proud I am that I had the honour to call him friend.

I have the honour to be,

Yrs sincerely

MEECHAM, Capt.

The Second Battle of the Odon may have been indecisive in its result, with British casualties and losses amounting to between 3,000 and 3,500 as opposed to those of the enemy, at around 2,000.

From Normandy to the Netherlands: Churchill tanks

of 6th Guards Tank Brigade and troops of the 10th Highland Light Infantry, 15th

(Scottish) Division, during the assault on Tilburg, Holland, 28 October 1944.

Image credit: Sgt Johnson, No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit. This is

photograph B 11419 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

But the 10th Battalion went on to play a full part in the liberation of Europe from Nazi tyranny, crossing the Rhine in Buffalo amphibians at Xanten at 2.00 am on 24 March 1945.

The now famous pipe tune that commemorated the event was penned by

the Battalion’s Pipe Major Donald Ramsay and Corporal J. Moore. The Battalion then

advanced on to the Elbe, making one final assault in Buffaloes to cross the

Elbe a few days before the surrender of German forces in Northern Germany. If

you happen to be musical and have pipes to hand you can find the music here

From the Exmouth Journal, Saturday 29 July 1944

As for Major George Palmer, the news of the death of this 28-year-old

‘grand sportsman’, as he was described in the local media, was met in the local

area with shock and sadness. His sporting friends remembered him as

a player ‘full of dash and courage’.

His elder brother, John Copplestone Palmer, had been previously wounded in North Africa but survived until 2002, when he died at the age of 89.

Also in the packet of documents that I received were many letters

written to console his family, showing how loved and respected George was by so

many people who knew him.

Of all the letters I found that this one from his sister Mary was the most heartrending.

A Norland Nanny – trained by Britain’s leading childcare institution – Mary was living at the time in Bradninch, just outside Exeter. She and her husband were running The Manor House, then owned by the Duchy of Cornwall, as a home from home for the children of those serving abroad, and welcomed the then Princess Elizabeth during a royal visit. They wanted somewhere which would take family groups together and not have to split the girls from the boys, which was the custom at the time.

Mary's letter was written to send George her best wishes for his 29th birthday on 18 July:

The envelope was

addressed to Major G.T. Palmer, C Coy, 10 Bn HLI, BWEE [?]

[No date]

My dear George

Many thanks for your letter. I hope the Beer & bread have reached you now! I was glad to hear from you. I would love to see you in a sporran!

If I am allowed to send parcels of food to France, I will send you a birthday cake (not fruity – no fruit!) but if there is a ban, goodness knows what I shall send! The children send their love and Gilliam will be writing to you. We have Anne Copland’s two children here, & they have had a spank on their behind! They are nice little children, but spoilt & whiny. Rosalind is much better, & even Anthony seems to realise that a loud roar doesn’t get him what he wants! I did like Anne – an awfully nice girl. Kathleen brought them over. She does seem to think you are rather nice! So does Mrs Bennett! (& this is a secret Nurse Betty!). To say nothing of your adoring sister!

We are swarming with babies at present. Can’t say No to children from London. They are mostly under two. Two of them have to sleep in prams in the dining room, as we have no other room. I have managed to get some extra help & we don’t do too badly, better off than people suffering from bombs – and our fighting men! Why don’t people think a bit? Do you know, several Mothers were refused rooms because they had babies – after travelling down from bad raids in London. It makes me wild with fury!

Two babies have arrived to be fed by the fire (10 p.m.) & my child is up in his cot & probably yelling like fury for a feed!! Mercifully they all sleep at night.

Bunty sends her love & so would the others if they were here. Sherry [1] has gone to bed! He sometimes wishes he hadn’t been discharged – babies everywhere!

Gillian’s godmother Beryl Tracy-Forterie [2] is here for a fortnight & I have given her a baby to look after!

Moira Thomson, Sherry’s Irish cousin – small, dark & pretty – (you know her?) is going to have a baby herself. David her husband, & Jacques [?] her brother (Unreadable) are in France too. Give them my love if you see them.

I must go & feed the baby!

All good wishes for your Birthday & many Happy Returns!

Best love & good luck

from Mary.

[1] Sherry was Mary’s

husband, Joseph Sherwood Arden Clarke.

[2] Beryl Adelaide

Furneaux Jenkis de Tracy Forterie emigrated to Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

This letter was in an

envelope postmarked Tiverton 14 July 1944, and returned with this stamped

message: IT IS REGRETTED THAT THIS ITEM COULD NOT BE DELIVERED BECAUSE THE

ADDRESSEE IS REPORTED DECEASED.

One can barely imagine

the sister’s feelings on reading that message.

George's body was removed from Baron sur Odon and reburied in the War Cemetery of Banneville-la-Campagne,

a village 10 kilometres east of Caen.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission certificate for George, showing Banneville-la-Campagne War Cemetery where he is buried. Image credit: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

For

the most part, the men buried at Banneville-la-Campagne War Cemetery were killed

in the fighting from the second week of July 1944, when Caen was captured, to

the last week in August, when the Falaise Gap had been closed and the Allied

forces were preparing their advance beyond the Seine. The cemetery contains

2,170 Commonwealth burials of WW2, 140 of them unidentified, and five Polish

graves.

The next post is for SIGNALLER RONALD YEATS (1916-44), who died in

Normandy on 8 August 1944, while serving with the 1/5th Battalion,

The Queen’s Royal Regiment (West Surrey) and the

Royal Corps of Signals. Like George, he is buried in the War Cemetery of Banneville-la-Campagne. You can read about him at

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2020/10/www2-75-gods-greatest-gift-remembrance.html

Comments

Post a Comment