WW2 75 – 19 April 1945 – A missing name: Lieutenant David Hubert Harvey-Williams MC (1926-45) Royal Horse Guards

Continued from 18 April 1945 – Death of a ‘Tankie’ in Italy.

SERJEANT FRANCIS EDWARD STEWARD (1918-45)

8th Battalion, Royal Tank Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2024/01/ww2-75-18-april-1945-death-of-tankie-in.html

The headstone

on David’s grave in Hamburg’s Ohlsdorf Cemetery. It bears the inscription THANK YOU, DARLING, FOR THOSE NINETEEN BLISSFULLY

HAPPY YEARS. GOD BLESS YOU

Just a few weeks before VE Day, the death of David Hubert Harvey-Williams on 19 April 1945 was recorded. He was only 19. Those two facts are tragic, and the absence of his name from Budleigh Salterton’s War Memorial only adds to the sad event.

The

Commonwealth War Graves Commission list of casualties, pictured above, notes

that he was buried in Hamburg Cemetery in Germany, and that he was the son of Robert

Harvey-Williams and Doris Harvey-Williams ‘of Budleigh Salterton’. His

service number was 3I59I9.

Thanks to Roz Hickman, Head of Local History at Budleigh’s Fairlynch Museum, I learnt that David’s mother, Doris Harvey-Williams, lived in Clinton Terrace and that his father Robert lived in Hertfordshire. They may well have separated by the time of David’s death because there was apparently a well publicised divorce case.

The Imperial College Operatic Society (ICOS) programme for its production of ‘HMS Pinafore’ includes on its membership list for 1981-82 the name of Miss D.J. Harvey-Williams, seen above. It’s likely that this was David’s mother.

Further investigation revealed that David’s father was the highly qualified physician and surgeon Robert Harvey-Williams MRCS Eng, LRCP Lon, FRCS Edin. He had arrived in Hitchin in April 1922, four years before his son David’s birth, and until 1930 he was a partner in the medical practice of J.H. & Marshall Gilbertson and Harvey-Williams at 81 Bancroft, a road running through the centre of the town of Hitchin, Hertfordshire.

The partnership dissolved in 1930 when the other two partners, Dr James Henry Gilbertson and his son Marshall, set up their own practice at 107 Bancroft.

According to Dr Gerry Tidy, a retired doctor and member of Hitchin Historical Society who became one of the town’s GPs in August 1975, the dissolution of the partnership came about because of Robert Harvey-Williams’ divorce.

A

photo showing the entrance to 118 Bancroft, the former surgery of Dr Robert Harvey-Williams. The building was demolished in 1958. Image credit: Zena Grant and Hitchin Historical Society

Robert set up in practice

on his own at 118, Bancroft, helped only by his dispenser and general factotum

John Moorcraft.

22 Bancroft in 1948. Image credit: Zena Grant and Hitchin Historical Society

He remained there until

in December 1935, he moved to 22 Bancroft, buying the building along with a

dentist, John Cranfield, and a solicitor, Major Lindsey. Robert was joined the

following year in his medical practice by a Dr James Smyth, a retired doctor

who had moved from Melton Mowbray to make his home in Hitchin.

On

the left is Dr R. Harvey Williams founder of the practice and first medical

superintendent of the Lister Hospital.

In addition to his work

as one of Hitchin’s GPs, Robert was also the first medical superintendent of the

town’s cottage hospital, known as the Lister Hospital.

Thanks to research by Hertfordshire local historian Zena Grant, it appears that Dr James Gilbertson had attended the independent Repton School in Derbyshire and it would be useful to know which school Dr Robert Harvey-Williams and his son David Hubert had attended; independent school archivists are a ready and valuable source of information and photos.

At the time of David’s death he had been on active service for only one year, conscription for all males aged between 18 and 41 having been introduced by Parliament at the outbreak of WW2.

And yet he was already an officer with the rank of Lieutenant. The chances are that the Harvey-Williams family, with a professional medical background and a second home in Budleigh Salterton, would have been financially comfortable enough for David to have attended an independent school with its own Combined Cadet Force. This would have provided him with sufficient military training to be seen by the authorities as ready officer material, particularly suited for entry to the regiment of the Royal Horse Guards, known as ‘the Blues’. This was a British Army unit which was part of a larger regiment, the Household Cavalry, the other unit being the Life Guards. Together, the two are described as the most senior regiments of the British Army.

Life Guards poster. The British artist was Eric Meade-King (1911-1987)

Horses may have had a role in recruitment for the Household Cavalry, as seen in this poster, and had even had a role in WW1. However a mechanisation programme was well in place by the 1930s. A training regiment based in Windsor gave up its horses in 1941 and became the Household Cavalry Motor Regiment, then the Second Household Cavalry Armoured Car Regiment and finally the Second Household Cavalry Regiment, abbreviated to 2HCR.

David would have been part of this unit which landed on the Normandy beachhead on 14 July 1944, acting as a lightly armoured highly mobile reconnaissance force.

The Second Household Cavalry Regiment’s war has been described in a review of historian Roden Orde’s book on the subject as a short and exciting one, from Normandy in July 1944 to Germany in May 1945. ‘Continuously on the advance and rarely out of contact with the enemy,’ the 2HCR was in the vanguard of the Guards’ Armoured Division. ‘Sometimes progress was slow and grinding, while at other times it was with exhilarating speed.’

Daimler Armoured Car, Mark II. Image credit: Wikipedia

The speed of its operations owed much to the use of Daimler armoured cars, built to a British design and capable of a maximum speed of 50 mph with a crew of three.

Daimler Dingo scout car on display in 2012 at the Eurosatory Museum, Paris. Image credit: Wikipedia

The Daimler Dingo scout car had been developed in parallel. With a crew of two it had a maximum speed of 55 mph. A typical late war reconnaissance troop in north-west Europe would have two Daimler Armoured Cars and two Daimler Dingo scout cars.

On the WW2 section of the Household Cavalry memorial we learn that David was a Troop Leader.

The six weeks following 2HCR’s arrival in Europe were spent in Northern France. On 15 August, troops of 2HCR were the first to cross the River Noireau and on 31 August, near Amiens, three troops captured three bridges over the Somme, well ahead of the rest of Allied forces, holding them until the Guards Armoured Division crossed.

Scenes of jubilation as British troops

liberate Brussels, 4 September 1944. Lt Col H A Smith, CO of 2nd Household

Cavalry Regiment, arrives in his Staghound armoured car. Imperial War Museum collection

By early September the Guards Armoured Division, led by 2HCR, were the first British troops to cross the frontier into Belgium. Brussels was taken on 4 September. Just under a week later, on 10 September a troop of 2HCR succeeded in reconnoitering the important bridge over the Escaut Canal, near Neerpelt, by means of which the whole British Army were to enter Holland.

Troops of 2HCR near the bridge over the river Tongelreep at Aalst, a village a few miles south of Eindhoven in the Netherlands. The British column came under fierce fire from 88mm guns, which were set up in the sports park in Eindhoven

Parachutes open overhead as waves of paratroops land in Holland during operations by the 1st Allied Airborne Army as part of Operation Market Garden

A week later,

until 27 September, David and his troop would have been involved in Operation

Market Garden.

This was an Allied military

operation fought in the German-occupied Netherlands from with the objective of

creating a 64 mile (103 km) salient into German territory with a bridgehead

over the Nederrijn (Lower Rhine River), creating an Allied invasion route into

northern Germany.

Armoured cars of 2HCR in advance

of the Guards Armoured Division of the British XXX Corps passing through the

town of Grave, SE of Nijmegen, 17 - 20 September 1944; Imperial War Museum photo B10133

Following Operation Market Garden troops of 2HCR were employed in the Nijmegen sector at a time when the Germans were desperately fighting the British advance to the Rhine. Nijmegen was at the front line and under frequent enemy fire. From November onwards, preparations were made for a massive invasion of Germany known as Operation Veritable, which began on 8 February 1945.

On 30 March the Guards Armoured Division with its tanks crossed the Rhine near Rees. Near Lingen, on 3 April, a troop of 2HCR found a bridge over the River Ems, unblown but strongly held by the enemy until it was stormed by men of the Guards Armoured Division.

At some point during the advance into Germany David’s leadership and bravery was recognised by the award of the Military Cross. The announcement of the award was made in a supplement of the London Gazette dated 7 July 1945, noting that he had since been killed in action.

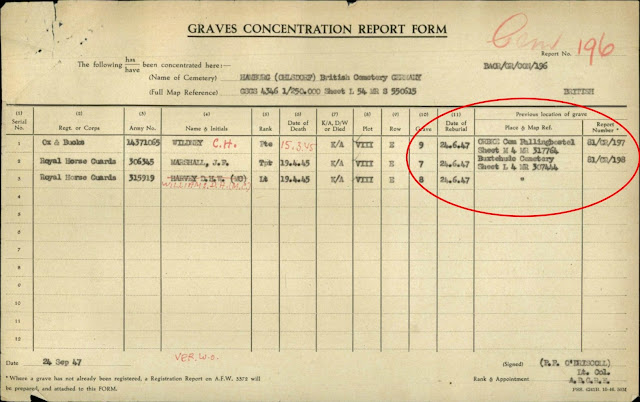

Graves Concentration Report Form dated 24 September 1947 Report No. BAOR/GR/CON/196

But where? The Graves Concentration Report Form, dated 24 September 1947 and published by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, tells us that his body was first buried in Buxtehude Cemetery, Buxtehude being a town some 45 minutes by road from Hamburg.

Image credit: www.billiongraves.com

This is a World War II cemetery in the middle of the woods outside the town. Kept by the local community, it contains the headstones of people fighting some of the last battles of World War II. For two years, David’s body would have lain alongside the bodies of German soldiers before being re-buried in Hamburg’s Ohlsdorf Cemetery on 24 June 1947.

Graves Concentration

Report Form dated 24 September 1947 Report No. BAOR/GR/CON/196

And he would not have been alone. The above document shows us that both Lieutenant Harvey-Williams MC and Trooper James Frederick Marshall, Service Number 306345, of 2/Royal Horse Guards, Household Cavalry, also 19 years old, were killed in action on the same day, 19 April 1945. Trooper Marshall’s body would also be re-buried at Hamburg. Unlike David’s grave, his headstone bears no personal inscription and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website gives no mention of his family details.

It is possible that both men died in the same

vehicle, perhaps destroyed by a mine. The retreating Nazi forces had left

various explosive devices on the approaches to Germany. Just over a week after

David and James’ deaths, the last Household Cavalry Officer to be killed in WW2,

Lieutenant Robin Tudsbery, lost his life along with Troopers Donald Cameron and

James Woodfield. Their Daimler armoured car was destroyed by a sea mine, designed

to sink shipping.

One final point which may explain the absence of David’s name from a war memorial. There was obviously confusion about his surname, judging by the variations on the above forms. The earliest form dated 24 September 1947 has HARVEY, DHW (MC) typed, crossed out and re-written as WILLIAMS, D.H. (MC) in a later version. Only on the form dated 20 August 1956 is David’s name correctly recorded.

Dr Robert Harvey-Williams outside his medical practice at 22 Bancroft, in Hitchin. Image credit: Zena Grant and Hitchin Historical Society

If his parents had remained together, perhaps living in Budleigh like

his mother, David’s name might have been added to the war memorial. But his

father, Dr Robert Harvey-Williams was still in Hitchin. He retired in December

1949, four years after his son’s death, a tragic event which had no doubt

affected him. After his retirement from the medical practice in Hitchin he made

his home in Kingston, Jamaica. Later he went to live in Ireland, where he died

in May 1967.

If his parents had remained together, perhaps living in Budleigh like

his mother, David’s name might have been added to the war memorial. But his

father, Dr Robert Harvey-Williams was still in Hitchin. He retired in December

1949, four years after his son’s death, a tragic event which had no doubt

affected him. After his retirement from the medical practice in Hitchin he made

his home in Kingston, Jamaica. Later he went to live in Ireland, where he died

in May 1967.

No member of the Harvey-Williams family has contacted me as yet. A former Budleigh resident, now living in Australia, told me that she knew of a Hugh Harvey-Williams who would have been born around 1946, with an aunt named Josie, who lived at Clinton Terrace. The above photo shows him on the far left, playing the guitar during a fancy dress party at Budleigh Salterton Tennis Club in around 1960.

According to a report in the Somerset County Gazette, a 59-year-old man with the same name, narrowly escaped death in a road accident in August 2006. He was living near Kingston St Mary, Taunton.

Hamburg’s Ohlsdorf Cemetery, David's final resting place. Image credit: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The next post is for

Comments

Post a Comment