AROUND THE TOWN AND OVER THE POND - 14. LOOKING BACK AT FAIRLYNCH: ADMIRAL PREEDY AND THE VICTORIAN INTERNET (2017)

Continued from

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2024/07/around-town-and-over-pond-13-looking.html

AROUND THE TOWN AND OVER THE POND

A walk around Budleigh Salterton to interest transatlantic visitors. Every so often there’s a diversion which may inspire you to visit places like East Budleigh, Exeter, Sidmouth, Colyton or even places in the United States and Canada.

The walk is set out in parts. Here’s the fourteenth part:

14. LOOKING BACK AT FAIRLYNCH: ADMIRAL PREEDY AND THE VICTORIAN INTERNET (2017)

Summary: How a retired

naval officer and Budleigh resident played a key role in building ‘the highway

of thought between the Old World and the New’.

The text in the above stained glass window reads: 'In

memory of George William Preedy CB, who when Captain of HMS Agamemnon with the

Captain of the USS Niagara successfully laid the first Transatlantic Cable

uniting Europe and America in 1858.'

Anniversaries make a good reason to stage exhibitions. In 2017 Fairlynch Museum staged an exhibition to celebrate former Budleigh resident Vice Admiral George William Preedy CB, born in 1817.

This distinguished 19th century naval officer is commemorated at All Saints Church in East Budleigh, where you can find his grave. A stained glass window in the church includes only a few lines about the feat for which the Admiral is most famous. The Museum’s exhibition explained it in more detail as well as dealing with other aspects of Preedy’s life.

This panel showing HMS Agamemnon meeting a whale mid-Atlantic was used to publicise the Preedy exhibition. It was painted by Joy Launor Heyes, a member of Budleigh Salterton Art Club

The exhibition ‘Admiral Preedy and the Victorian Internet’ opened at Fairlynch Museum on Friday 14 April 2017. Prior to the opening, on Sunday 9 April, a talk under the same title was given by Fairlynch Museum Chairman Trevor Waddington in County Hall, Topsham Road, Exeter.

The talk was part of the Devon-Newfoundland Heritage Forum organised by the Devonshire Association and the Devon Family History Society (DFHS) from 3-16 April.

Above is the first of a series of panels designed for the Preedy exhibition at Fairlynch Museum. For his achievement in helping to lay the Transatlantic Telegraph cable, Preedy was honoured by Queen Victoria as a Companion of the Order of the Bath, entitling him to the letters CB after his name.

Image credit: Wikipedia

The Queen had been on the British throne for just over 20 years. This portrait of her in 1859, part of the Royal Collection, is by the German painter Franz Xavier Winterhalter. Next to it is the badge of the Order of the Bath which she awarded to Captain Preedy, as he then was.

To coincide with the Preedy

exhibition in 2017, the Museum’s Costume Department staged a special display of

Victorian costumes, depicting a scene with a postman of the time bringing a

telegram.

Brought up in Worcestershire in a family with military links, Preedy joins the Royal Navy aged 11. As a 15-year-old Midshipman he serves in the Navy’s campaign against the slave trade

This panel refers to the slave ship Joaquina.

The vessel, carrying 348 Africans, is mentioned in an incident of 10 November 1833. On that

occasion it was captured by the British schooner HMS Nimble after a

battle near the Isle of Pines, Cuba – now called Isla de la Juventud. The Spanish captain and two

captive Africans were killed in the battle, another African died later of his

wounds, and Joaquina sank.

The account of the episode was

graphically described by Nimble’s Commander, Lieutenant Charles Bolton,

in a letter written a week later and dated 16 November:

‘I beg to acquaint you, that I arrived this day, at

this port, in his Britannic Majesty's schooner, Nimble, with the Spanish

slave- schooner, Joaquina, captured on the morning of the 10th inst.

off the Isle of Pines. At daylight on the 10th inst. a sail was discovered

about 9 or 10 miles to leeward, standing in for land. All sail was immediately

made in chase, and having greatly the superiority of sailing, I soon made her

out to be a large schooner, which we were closing very fast. When within three

or four miles the stranger, perceiving there was no chance of escaping by

sailing, wore round, shortened sail, and hove-to to receive us ; being then

seven or eight miles from the south-west point of the Isle of Pines. I soon

afterwards took in studding-sails and square sail, and prepared for action,

still bearing down upon him; he then hoisted Spanish colours and fired a blank

gun, when I hoisted our colours, and as soon as we were within musket-shot (to

ascertain positively what he was) I ordered two muskets to be fired over him,

which he returned by a well-directed shot from a long 12-pounder.

I immediately opened fire upon him, closing as

quickly as possible. The wind now becoming very light, he continued receiving

and returning our fire until within half pistol-shot, when, having received two

8-pound shot between wind and water, several through his upper works and sails,

his mainmast cut nearly through, and rigging much damaged, the captain

desperately wounded (since dead), he struck his colours, and cried for quarter.

His defence was most obstinate and desperate, continued nearly an hour, and he

fought worthy of a better cause.’

Above: Slave chains on display in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter. The Liverpool ship Brooks was used in the slave trade in 1781. In 1788, abolitionists in Britain commissioned a drawing of how people were squeezed on board the ship to raise awareness of the inhumanity of the slave trade. Image credit: Wikipedia

The Act of Parliament to abolish the British slave trade was passed on 25 March 1807. It was the culmination of one of the first and most successful public campaigns in history. The Blockade of Africa began in 1808 after the United Kingdom outlawed the Atlantic slave trade, making it illegal for British ships to transport slaves, and the Royal Navy’s West Africa Squadron was set up to enforce the ban.

This painting, ‘The Slave Ship’, originally titled ‘Slavers Throwing overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhon coming on’, is by the British artist J. M. W. Turner. It was first exhibited at The Royal Academy of Arts in London in 1840, and is part of the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA. As a public display of a horrific event the work was intended to evoke an emotional response to the inhumane slave trade still occurring at that time in other parts of the world.

Preedy’s naval career as a Midshipman in the Mediterranean

He is promoted to Lieutenant and sees service in

the Pacific

Commander Preedy serves in the Crimean War, is

mentioned in despatches and promoted to Captain

Captain Preedy in uniform Image credit: Lintorne Wightman

The background to the laying of the Transatlantic Cable by British and American warships

Meeting the USS Niagara in mid-Atlantic with no modern technological aids such as radar was a remarkable feat

There have been six Royal Navy

ships named Agamemnon, including the most recent, a nuclear submarine. The ship commanded by Preedy was the second

in the series

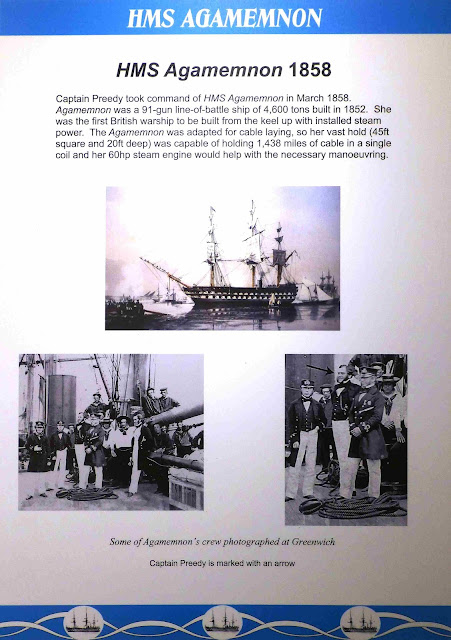

Very few images of Admiral Preedy exist. This photo, showing him in 1858 with the crew of HMS Agamemnon — he is standing fourth from the left, with no cap — was taken by A.J. Melhuish (1829-95), a noted photographer of the time who had a studio in Blackheath, London

Some technical details of the cable laying

There have been nine

ships of the US Navy named Niagara. The steam frigate USS Niagara

which took part in the Transatlantic Cable operation was the second of the

series. Launched three years earlier, it was commanded by Captain William L. Hudson. Later in 1858 it took part in an

anti-slavery operation, rescuing 271 Africans, although 71 died, suffering from

scurvy and dysentery.

Difficulties of the operation

Above: The Agamemnon, with the Atlantic cable on

board, in the great storm on 20 and 21 June, 1858. Reproduced by Leslie's from

the Illustrated London News, in

turn reproduced from an original drawing by Henry Clifford

‘Our ship, the Agamemnon, rolling many

degrees, was labouring so heavily that she looked like breaking up,’ recalled

one member of the party. ‘The massive beams under her upper deck coil cracked

and snapped with a noise resembling that of small artillery, almost drowning

the hideous roar of the wind as it moaned and howled through the rigging. Those

in the improvised cabins on the main deck had little sleep that night, for the

upper deck planks above them were “working themselves free”, as sailors say;

and, beyond a doubt, they were infinitely more free than easy, for they groaned

under the pressure of the coil, and availed themselves of the opportunity to

let in a little light, with a good deal of water, at every roll. The sea, too,

kept striking with dull heavy violence against the vessel’s bows, forcing its

way through hawse holes and ill closed ports with a heavy slush; and thence,

hissing and winding aft, it roused the occupants of the cabins aforesaid to a

knowledge that their floors were under water, and that the flotsam and jetsam

noises they heard beneath were only caused by their outfit for the voyage

taking a cruise of its own in some five or six inches of dirty bilge. Such was

Sunday night, and such was a fair average of all the nights throughout the

week, varying only from bad to worse.’

The breaking adrift of the coal on board HMS Agamemnon, a painting by Henry Clifford. Agamemnon

keeled over to 45 degrees in either direction during the storm on 21 June 1858.

Image credit: Wikipedia

Things were indeed to worsen, with many members of

the crew severely injured, crushed by displaced cargo and coal supplies.

‘The Agamemnon took to violent pitching, plunging steadily

into the trough of the sea as if she meant to break her back and lay the

Atlantic cable in a heap. This change in her motion strained and taxed every

inch of timber near the coils to the very utmost.

The upper deck coil had strained the ship to the very utmost, yet still held on

fast. But not so the coil in the main hold. This had begun to get adrift, and

the top kept working and shifting over from side to side, as the ship lurched,

until some forty or fifty miles were in a hopeless state of tangle, resembling

nothing so much as a cargo of live eels.’

Image credit: Wikipedia

This coloured print shows a whale crossing over the telegraph

cable and is one of the best known images published about HMS Agamemnon’s

epic 1858 voyage. The paying-out

machinery used to lay the cable is visible on a temporary structure that has

been added to the ship. A fender encircles the stern to prevent the cable from

becoming entangled with the ship's propeller. The ship's crew is gathered on

the top deck to watch.

Some of the first messages sent by the Atlantic Telegraph

‘Directors of Atlantic Telegraph Company, Great

Britain, to Directors in America. Europe and America are united by telegraph.

Glory to God in the highest; on earth peace, good-will towards men.’

As seen in the above panel, a tickertape recording of Queen Victoria's message to the President of the United States, James Buchanan, was transmitted by submarine cable from Ireland to Newfoundland on 16 August 1858. The text of the tickertape reads:

‘TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, WASHINGTON

The Queen desires to congratulate the President upon

the successful completion of this great international work, in which The Queen

has taken the deepest interest.

The Queen is convinced that the President will join her in fervently hoping

that the electric cable, which now connects great Britain with the United

States, will prove an additional link between the nations, whose friendship is

founded upon their common interest and reciprocal esteem.

The Queen has much pleasure in thus communicating with the President, and

renewing to him her wishes for the prosperity of the United States."

THE PRESIDENT’S REPLY. August 16, 1858

“Washington City. To Her Majesty, Victoria, Queen of Great Britain:—The

President cordially reciprocates the congratulations of Her Majesty, the Queen,

on the success of this great international enterprise, accomplished by the

science, skill, and indomitable energy of the two countries. It is a triumph

more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than ever was won by

conqueror on the field of battle. May the Atlantic Telegraph, under the

blessings of Heaven, prove to be a bond of perpetual peace and friendship

between the kindred nations, and an instrument designed by Divine Providence to

diffuse religion, civilization, liberty, and law throughout the world. In this

view will not all the nations of Christendom spontaneously unite in the

declaration, that it shall be forever neutral, and that its communications

shall be held sacred in passing to the place of their destination, even in the

midst of hostilities?

JAMES BUCHANAN.”

As noted above, celebrations on the success of the

Atlantic Cable were wild in America. Fireworks in New York nearly destroyed the

City Hall.

All the officers of HMS Agamemnon and the USS

Niagara were awarded medals

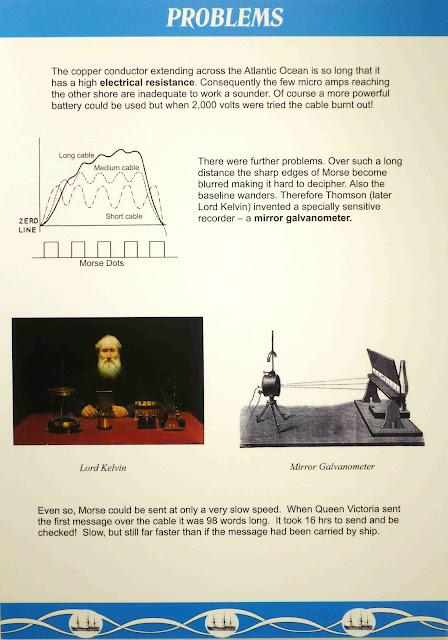

Problems

Queen Victoria’s message of 98 words took 16 hours

to send across the Atlantic. The 1858 cable lasted only a few months, but it

had been successful and would be replaced with improved versions.

Cable technicalities

Morse code, invented by the American Samuel Morse in

around 1837, was first used for telegraphy in 1844.

On 9 November 2017, children from St Peter's Church

of England Primary School, Budleigh Salterton, visited the Admiral Preedy exhibition

and learned about International Morse code.

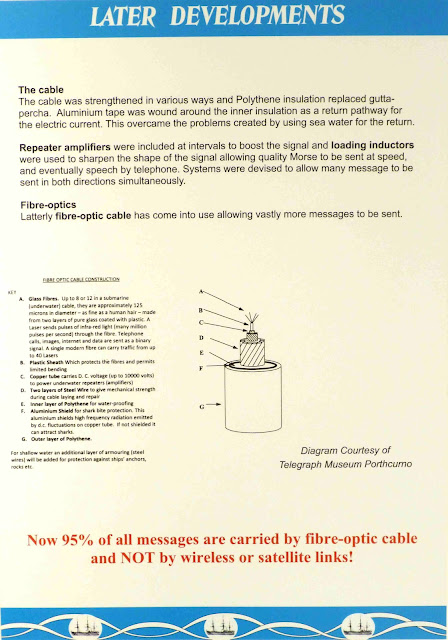

Later developments: from gutta-percha to

fibre-optics

Preedy

was married in 1864 and retired from the Royal Navy in 1874, aged 57. He was

promoted to Rear Admiral.

Retirement in Budleigh

Salterton

He and his family are

listed in the 1891 Census as living at Park House in Little Knowle, on the western side of Budleigh Salterton.

Vice Admiral Preedy in later years

He is buried in the family grave – K21 7 – in All Saints’

churchyard, East Budleigh:

George William Preedy 20 Feb 1817–30 May 1894;

Mabel Caroline Preedy 4 Aug 1871–30 Jan 1886;

Elizabeth Ann Hartle Preedy, wife, 11 April 1837–16 March 1906.

Admiral Preedy’s remarkable feat

is commemorated in the fine Preedy window in All Saints Church, East Budleigh. It

appropriately depicts the storm over the Sea of Galilee mentioned in the New

Testament.

On 19 June 2017, children from St Peter's Church

of England Primary School, Budleigh Salterton, accompanied by Deputy Head Phill

Lee, visited Fairlynch to see the Admiral Preedy exhibition. They met Steve Manning playing the role of HMS

Agamemnon crew member Isaac and learned about 19th century

naval traditions, including sea shanties.

Admiral Preedy’s great-great grandson Lintorne

Wightman made a special journey from Vienna to open Fairlynch Museum’s exhibition in honour of his ancestor.

He kindly

allowed Admiral Preedy’s prayer book to be displayed as one of the precious

artefacts on display in the exhibition.

Other artefacts on loan included a copy of the

pennant flown by HMS Agamemnon, and a section of the 1858 cable. The 12.75

metre-long originals of the pennants are in the National Maritime Museum (UK)

and the Smithsonian Institute (USA). Tiffany & Company of New York sold

thousands of the cable samples at 50 cents each, guaranteed as authentic.

Max and Louisa Wightman great-great-great-great

grandchildren of Admiral Preedy, were guests of honour at the exhibition

preview on Thursday 13 March 2017. They

are shown next to a painting by Budleigh Salterton artist Joyce Dennys.

The beaches of Budleigh Salterton and Menuel, pictured with the 'FAB' link logo

The Admiral Preedy exhibition coincided with the ‘FAB’ project (France –

Alderney – Britain) of building an electrical interconnector underwater and

underground between France and Great Britain.

The project will consist of one pair of electrical

cables, a converter station at each end, and connections into the high voltage

grids at each end. The connection will be made over nearly 220 km between the

electrical substations at Menuel, on the Cotentin peninsula in France, and that

near Exeter, in Devon. FAB Link Limited was

a principal sponsor of the Admiral Preedy exhibition in 2017. You can read more

about the project at https://www.fablink.net/

Pictured above are Chris Jenner, Development Manager with FAB Link Limited, and Lintorne Wightman at the exhibition preview on Thursday 13 March 2017. In the background is Trevor Waddington OBE, Chairman of Fairlynch Museum and designer of the Admiral Preedy exhibition.

You can read more about the Atlantic Telegraph at https://atlantic-cable.com/

I was so impressed by Admiral Preedy’s feat that I composed these verses in his honour.

1. Now let us sing of heroes, who sailed

the ocean blue,

And of a Budleigh worthy, and don’t forget his crew.

Two hundred

years ago it was - from rural Worcestershire -

That Georgie William Preedy came:

A nautical high-flier.

He passed all

his exams, of course, and rose up through the ranks.

We’re sure that

to an army life he would have said

‘No thanks!’

Chorus

So let us raise

our glasses to our Admiral Preedy!

We wrote this

little song to mark his bicentenary.

2. A Royal Navy

midshipman in 1828

He did his bit

to fight the trade that Wilberforce did hate.

On board the frigate Ranger he performed his very best

To help abolish slavery:

A crime that we detest.

Our Navy at that period was proud to rule the waves

And liberate poor people who’d been captured and made slaves.

Chorus

So let us raise

our glasses to our Admiral Preedy!

He did his bit

like Wilberforce to combat slavery.

3. In 1853 aboard the Duke of Wellington.

A first-rate

Royal Navy ship; he found it rather fun.

As

second-in-command he gained respect from all he met.

With sail and

steam propelling her

The ship was

quite a threat.

In time he

gained promotion to the ship which made his name.

It was the

Agamemnon which would really bring him fame.

Chorus

So let us raise

our glasses to our Admiral Preedy!

Distinguished

officer of our redoutable Navy.

4. By 1858 he is the captain of the ship.

Its technical

description? That’s something we can

skip.

A 91-gun

battleship, equipped with sail and screw,

And many other

features

That I won’t

impose on you.

A popular

commander with a pleasant-sounding voice,

Our Georgie was

by all accounts, it seems, the sailors’ choice.

Chorus

So let us raise

our glasses to our Admiral Preedy!

So famous for

commanding Agamemnon’s company.

5. Now Queen Victoria it was who sat upon the throne.

It was a time,

you realise, when people couldn’t phone.

The Queen was

told ‘Your Majesty, our scientists desire

To send a

message overseas,

And all we need

is wire!

And thanks to

many clever men, including Mr Morse,

We have the

means to do it, though we need a ship of course!’

Chorus

So let us raise

our glasses to our Admiral Preedy!

He helped to

pioneer Victorian telegraphy.

6. The Agamemnon put to sea with many tons of cable

It sailed from

Valencia but wasn’t very stable.

A storm arose

and almost caused the ship to lose its load.

But Captain

Preedy kept his cool;

To him all

lives were owed.

East Budleigh’s

parish church is where the saga is recalled:

As testament to

bravery a window was installed.

Chorus

So let us raise

our glasses to our Admiral Preedy!

The bravest

naval officer who ever put to sea.

7. The Agamemnon carried on, but almost hit a whale.

An episode

depicted by the men who told the tale.

Amazingly it

met as planned its Yankee sister ship.

Mid-way across

‘The Pond’ they met

And talked

about their trip.

Then cable ends

from both the ships they finally did splice.

They had a

little problem there, and had to do it twice.

Chorus

So let us raise

our glasses to our Admiral Preedy!

We think he’s

just as great as Guglielmo Marconi.

8. And finally it all was fixed and messages were sent:

A transatlantic

chat between the Queen and President!

They had a few

more problems and the link began to fail.

The engineers

did scratch their heads,

And some, I’m

sure, did wail.

They had to

wait a few more years for permanent success;

Brunel’s ship

the Great Eastern was a help, I must confess.

Chorus

So let us raise

our glasses to our Admiral Preedy!

His story is a

thrilling one, I think we all agree.

9. And as for Captain Preedy, he was honoured as we know,

The world’s a

smaller place today as human contacts grow.

The Navy made

him Admiral, Commander of the Bath.

From rural

Worcestershire to this

It was a hero’s

path.

I think of

world wide webs to see his house in Little Knowle;

I think of

human progress since that age of steam and coal.

Chorus

So let us raise

our glasses to our Admiral Preedy!

He was a worthy

citizen of East Devon’s Budleigh.

If you feel like a sing-song type of sea shanty

based on ‘In praise of Admiral Preedy’ you could use the tune of Miss Susie Had A Baby,

His Name Was Tiny Tim’.

Comments

Post a Comment