WW2 100 – 11 June 1941 – 'A German platoon fired a salute of honour over the grave': Flying Officer Peter Harold Howard Pritchard (1921-41)

Continued from 10 June 1941 'A Vaseful of Remembrance':

SERGEANT JOHN LAKE ENDICOTT (1921-41)

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2020/12/ww2-75-10-june-1941-vaseful-of.html

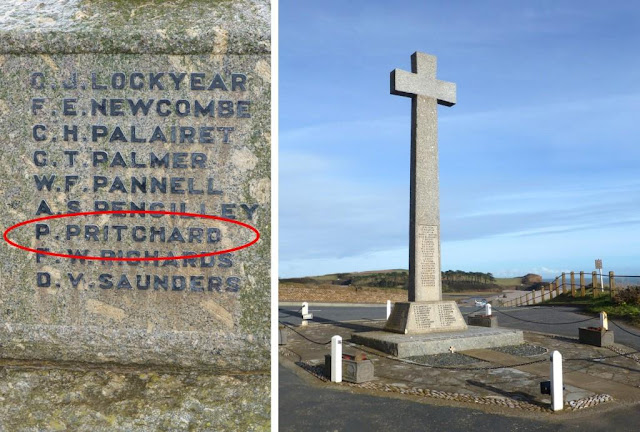

Identifying

Peter, who died at the age of 19 while on a minelaying mission, proved difficult:

with just the initial P on Budleigh’s war memorial for guidance, the

Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) database yielded only two servicemen,

both named Peter. For a long time I

included him as one of my ‘orphans’ – Budleigh-linked WW2 servicemen about whom,

sadly, barely anything is known. Finally with immense help via Ancestry from Budleigh

resident Carolyn John, Peter Pritchard’s story emerged.

It

seems that the Pritchard family was based mainly in London, but details uncovered

by Carolyn included Peter’s address as ‘Cove’, Budleigh Salterton. Evidently this fine 19th century

house at 2 West Terrace was a holiday home for the family, which would explain

why Peter’s name is included on the war memorial.

Peter was the younger of two

children born to a successful London doctor, Harold Pritchard MD, FRCP and his

wife Edith Margaret née Little, living in Marylebone. Dr Pritchard was born at

Chester in 1876, and graduated from London University as a Doctor of Medicine

in 1906. Evidently he served as a medical officer during WW1, for he gained the

rank of Wing Commander in the Royal Air Force, being appointed a Fellow of the

Royal College of Physicians in 1926.

The West London Hospital building in Hammersmith. Image credit: Wikipedia

By 1938 he had retired. He died in

about November of that year, aged only 61, just before the outbreak of war. An

obituary in the British Medical Journal of 10 December 1938 describes him as Emeritus

Physician at the West London Hospital.

A WW1 VAD

poster designed by Budleigh artist Joyce Dennys, herself a VAD nurse. Could the Pritchard and Dennys families have

met in Budleigh Salterton?

Peter’s mother, it seems, came

from a Glasgow shipping family. It may well be that the Pritchards had

regularly stayed in Budleigh as early as WW1, for records show that a 29-year-old

Mrs Edith Margaret Pritchard had been engaged as a VAD (Voluntary Aid

Detachment) nurse in South Devon on 17 September 1915.

Bletchley Park’s Hut 4 where Rosemary would have worked on naval intelligence. Image credit: Wikipedia

Peter’s elder sister Rosemary,

born in 1918, worked at Bletchley Park during the war and would become a well

known figure in Foreign Office circles; her two marriages to diplomats, firstly

to Sir Con O’Neill and then to Sir Terence Garvey, would take her to

interesting locations including Egypt, China, India and Russia. Details of her life published in obituaries following

her death on 17 August 2011 were helpful in writing Peter’s story.

RAF Cranwell, College Hall. Image credit: Wikipedia

Peter himself chose to join the RAF at the outbreak of war, perhaps following his father’s example. He is recorded as having trained as a flight cadet at the Royal Air Force College which had been formed in November 1919 at Cranwell, Lincolnshire, presumably after leaving his public school. The Royal Air Force tended to recruit its officers from the public schools and just 14 per cent of officer cadets at Cranwell between 1934 and 1939 came from grammar or state schools.

Peter was commissioned as Pilot Officer on 14 July 1940, as announced in the London Gazette of 6 August that year. He was later promoted to Flying Officer, though I have not found that announcement in the London Gazette.

Badge of Squadron 61. The figure of the Lincoln imp in Lincoln Cathedral associates the Squadron with the district in which it was re-formed in 1937 and where it spent most of its active days in WW2. ‘Thundering through the clear air’ is the translation of the Latin motto ‘Per Purum Tonantes’. Image credit: www.rafht.co.uk

The RAF’s No. 61 Squadron which he joined had started life in 1917 as one of the first three single-seater fighter squadrons of the London Air Defence Area intended to counter daylight air raids during WW1. The Squadron was re-formed on 8 March 1937 as a bomber squadron, and in WW2 flew with No. 5 Group, RAF Bomber Command.

WW2 buildings still visible at RAF Hemswell, which opened as a bomber base in 1937. It closed 30 years later in 1967. Image credit: Richard Croft - Wikipedia

In the early stages of the war, Squadron 61 was based at RAF station Hemswell, near Gainsborough, Lincolnshire. Bomber Command had been formed in 1936, and on 31 December that year, Hemswell was opened as one of the first airfields within No.5 Group of the newly formed Command.

No.144 Squadron arrived on 9 February and No.61 Squadron a month later on 8 March 1937, equipped with Avro Anson and Hawker Audax aircraft. Bristol Blenheim light bombers replaced these by January 1938 and they were completely re-equipped with Handley Page Hampdens by 20 March 1939.

A Handley Page Hampden Mark I, AT137 'UB-T', of

No. 455 Squadron RAAF based at Leuchars, Fife, Scotland (UK), in flight above

clouds, May 1942. Image credit: Imperial War Museums: Photograph COL182

This Hampden twin-engine medium bomber

manufactured by the British firm of Handley Page Limited was the aircraft in

which Peter would have flown from the start of the war until July 1941. It had

a pilot, navigator/bomb aimer, radio operator and rear gunner. Conceived as a

fast, manoeuvrable fighting bomber it was praised for being ‘extraordinarily

mobile on the controls’. Pilots were provided with a high level of external

visibility, assisting the execution of steep turns and other manoeuvres. But it

was often referred to by aircrews with names like the ‘Flying Suitcase’ because

of its cramped crew conditions.

The instrument panel and flying controls of a

Handley Page Hampden. Image credit:

Handley Page photographer. Photograph CH 1207 from the collections of the

Imperial War Museums/Wikipedia

‘I did my first flight and first tour on Hampdens,’ recalled former WW2 pilot Wilfred ‘Mike’ Lewis in a memoir published by the Bomber Command Association. ‘A beautiful aeroplane to fly, terrible to fly in! Cramped, no heat, no facilities where you could relieve yourself. You got in there and you were stuck there. The aeroplane was like a fighter. It was only 3 feet wide on the outside of the fuselage and the pilot was a very busy person. There were 111 items for the pilot to take care of because on the original aircraft he had not only to find the instruments, the engine and all that, but also he had all the bomb switches to hold the bombs'. The maximum range was 850 miles, with a payload of 4,000lbs. A distance of 1,100 miles could be reached with a payload of 2,000lbs.

Early missions for 61 Squadron focused on the North

Sea. A detachment was based in late 1939 at RAF Wick at the north-eastern

extremity of the mainland of Scotland, and the Squadron's first operational

mission was on 25 December 1939, comprising an armed reconnaissance over the

North Sea by 11 Hampden bombers.

The Squadron lost its first aircrew on 7 March 1940 when a Hampden Mk1 bomber crash landed at RAF Digby in Lincolnshire after returning from a patrol to attack the Luftwaffe base at Sylt, one of the German Frisian Islands.

A Heinkel He 59 seaplane. During the first months of WW2, the He 59 was used as a torpedo- and minelaying aircraft. Such seaplanes were used by the ‘Seenotdienst’ (sea rescue service), a German military organization formed within the Luftwaffe to save downed airmen from emergency water landings. Image credit: www.military.wikia.org

The island was visited again a fortnight later on the night of 19 March, when 20 Hampdens from 61 Squadron were among the first Bomber Command aircraft to drop bombs on German soil during WW2. The target was the Hörnum seaplane base, in retaliation for the Luftwaffe’s attack on Scapa Flow earlier in the month.

Squadron 61 sent Hampdens on further regular missions during 1940, including, on the evening of 11 May, the first major bombing raid on the German mainland, when the target was Mönchengladbach. This was in response to the invasion of Belgium, which had taken place the day before. The bomber crews were attempting to disrupt German troop movements on roads and rail lines in the area, especially the city's railyards.

Siemensstadt was the headquarters of the Siemens

electrical company, where products like this 1940s searchlight were

manufactured. As a leader in the German electrical industry, Siemens’ revenue –

like that of other major companies – increased continuously from 1934 and

reached its peak during the war years. Image credit: Siemens Historical

Institute

The Squadron was also involved in the first bombing raid on Berlin during the night of 25/26 August 1940. Six of its Hampdens were among the 95 aircraft dispatched to bomb Tempelhof Airport near the centre of Berlin and the industrial district of Siemensstadt, in retaliation for the German bombing of London.

Gathering information about the number and frequency of missions undertaken by 61 Squadron it’s impossible not to be overwhelmed by a sense of awe at the conditions in which Bomber Command airmen like Peter operated – and indeed airmen of every nationality who took part in these grim missions. A total of 57,205 members of RAF Bomber Command or airmen flying on attachment to RAF Bomber Command were killed or posted missing in WW2. Six Hampdens from 61 Squadron alone with their four-man crews were lost on missions over Europe just in the four weeks of June 1940.

Enemy losses were just as shockingly high. The World War II Database records that 424 of the Luftwaffe’s 1,380 bomber aircraft were lost on operations between July and September 1940. A total of 216 Luftwaffe airmen were killed just in June 1940.

Transporting mines to aircraft by trolley Image credit: www.rcaf434squadron.com

The minelaying mission over the North Sea during which Peter lost his life was one of hundreds undertaken by No.61 Squadron. From the start of WW2, Britain and Germany made significant use of aerial minelaying, with mines dropped by parachute in bays and sea lanes.

Codenames were given to the various areas for bombing and minelaying operations, based first on gardening and then expanding into seafood

The missions were known colloquially as ‘gardening’, with code names given to areas in which the mines were dropped. Some people thought of them as an easy option or ‘a piece of cake’, and it’s true that in some ways a ‘gardening’ mission was a relief from flying through the dazzle of searchlights and hail of murderous flak over the heavily defended cities of enemy territory. But low flying over water at night, often in virtually no moonlight, was certainly no ‘piece of cake’.

An enemy flak barge in Kiel Harbour Image credit: www.rcaf434squadron.com

The missions were usually undertaken by one single aircraft, giving the crew an uneasy sense of isolation. Cloud would often prevent them from checking to see that the parachutes had opened. It was essential for the pilot to steer an accurate and steady course, while the navigator and bomb-aimer had to have a high level of concentration to ‘sow’ the mines in the correct location. Needless to say, all members of the crew had to be on full alert for spotting coastal flak, ship-mounted artillery and the odd enemy night-fighter. Tiredness could have fatal consequences.

The Bomber Command Research Group, on its Facebook page, quotes from a Bomber Command Report of 1941. ‘It is not unusual for the mine-laying aircraft to fly round and round for a considerable time in order to make quite sure that the mine is laid exactly in the correct place. It calls for great skill and resolution. Moreover, the crew does not have the satisfaction of seeing even the partial results of their work. There is no coloured explosion, no burgeoning of fire to report on their return home. At best all they see is a splash on the surface of a darkened and inhospitable sea.’

On the evening of 11 June 1941, Hampden bomber AD727 took off at 10.45 pm from RAF Hemswell to lay mines in Kiel Bay, codenamed Quinces Region. Peter was at the controls as Pilot Officer; his fellow-crew members were Pilot Officer Frederick Arthur Caunter-Jackson, wireless operator Sergeant Patrick Joseph Breene, and Flight Sergeant John Bestwick. Whether or not they completed their mission is not known, for the aircraft was shot down by enemy flak and crashed into the sea off Buelk, north of Kiel Bay.

The Danish island of Lolland Image credit: https://wikitravel.org

Two months later, on 12 August 1941, Peter’s body was found washed ashore at Maglehøj Strand, on the shore of Lolland, one of Denmark’s islands in the Baltic Sea. He was buried on 15 August in the churchyard of Kappel, a small village in the south-west corner of the island, some 13 kilometres south of Nakskov, with, as the Danish website AirmenDK puts it, ‘all the military honours which the Germans still at that time showed their fallen adversaries’.

A German chaplain by the name of Graef officiated at the graveside, and at the end of the ceremony a German platoon fired a salute of honour over the grave. Later the Germans placed a cross there with the inscription ‘Hier ruht der englische Flieger Pritchard’.

Left: The cross placed by the Germans. It was taken away in 1942, when the Parish Council of Kappel erected the marble headstone, now next to the CWGC headstone erected on 4 September 2000. The inscription reads: 'Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.' Image credit: https://www.airmen.dk/a042001.htm

Peter’s headstone, located between the church and

the brick building, is on its own, in one of two plots of Commonwealth war

graves in Kappel churchyard.

Image credit: Commonwealth War Graves Commission

A separate plot of these three headstones is located at

the far end of the churchyard. Two commemorate simply an unidentified airman;

the third marks the grave of an Australian, Flight Sergeant Norman Lindsay Newell,

who died on 16 February 1944.

Of Peter’s crew, John Bestwick’s grave is at Kiel War Cemetery. The bodies of Sergeant Breene and Pilot Officer Caunter-Jackson were not recovered but they are remembered at Runnymede Memorial.

The sacrifice of Peter and his crew was not in vain. The RAF's postwar analysis of Bomber Command's efforts, had this to say: ‘The main contribution which the strategic air forces made in the conduct of sea warfare was in the minelaying campaign. During the war Bomber Command laid 47,000 mines, which were responsible for sinking or damaging over 900 enemy ships. The Command was in fact responsible for over 30% of sinkings inflicted on enemy merchant shipping in northwestern waters.’

Finally, it’s good to see from these two recent

photos sent to me that Peter’s grave on Lolland is being looked after. Searching

for Kappel churchyard on a map of the area, you can see that it’s clearly rather an isolated

spot.

The next post is for PRIVATE STANLEY JOHN HOLLOWAY (1914-41), who

died on 3 July 1941 while serving in the 12th Battalion of the

Devonshire Regiment. You can read

about him at

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2020/12/ww2-75-3-july-1941-our-beloved-son.html

Comments

Post a Comment