WW2 100 – 10 June 1941 – A Vaseful of Remembrance – Sergeant John Lake Endicott (1922-41), 118 Battery, 30 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment

Continued from 22 May 1941

The sad story of the Fighting G: Petty

Officer Frederick William Pannell (1907-41)

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2020/12/ww2-75-26-may-1941-sad-story-of.html

John Endicott and Elihu Yale plaque, near the John Adams Courthouse, Boston, Massachusetts, USA Image credit: Daderot/Wikipedia

For

many people, especially Americans, John Endicott is famous as one of the early 17th

century European settlers of the New World. He succeeded East Budleigh-born Roger

Conant as governor of Salem, and became the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay

Colony. He has long been recognised as a Devonian and in his reputed birthplace

of Chagford on Dartmoor, there’s even a house named after him.

I don’t know whether John Lake Endicott, listed on Budleigh Salterton’s War Memorial, was a descendant of his famous namesake, but he was certainly a Devonian. His father Ernest William Endicott was born in 1880 in the Dartmoor town of Moretonhampstead, and John himself was born in Newton Abbot.

Devonshire Regiment cap badge

So it’s no surprise to find that in

WW2 he started off in the Devonshire Regiment, as indicated by his Service Number

of 5622265. Between 1920 and 1943, when the system changed, the Devonshire

Regiment was allocated numbers 5,608,001-5,662,000.

John’s rank of Sergeant at the relatively young age of 19 would indicate that he was well motivated as a soldier. Was there a strong military tradition in the family? One uncle, Lance Corporal Alfred Thomas Endicott, a granite mason from Moretonhampstead, was a member of the Devonshire Regiment’s 1st Battalion when he was killed at Arras, France, during WW1 in April 1917.

Another uncle, Frederick Woolley Endicott, was a regular sailor with the Royal Navy, and had died in February,1915, while serving as Chief Yeoman of Signals on HMS Colossus.

Cap badge of the Royal Artillery Regiment

At

some stage in the early part of WW2, John transferred to the Royal Artillery,

and in 1941 was serving with 118 Battery of the 30th Light

Anti-Aircraft Regiment. I am not a military historian, and only after much

scrabbling on the internet did I discover that this unit took part in the 1944

Italian campaign.

But at the time of John’s death, on 10 June 1941, the 30th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery, was based in the East of England. Raised in August 1939, it had its headquarters in Ipswich, with its three artillery batteries deployed to protect ten RAF bases across East Anglia. The flat landscape of that part of England was ideal for airfields, but its proximity to the Continent made them vulnerable to enemy attack.

Stiffkey marshes Image credit: Hugh Venables / Stiffkey Salt

Marshes / CC BY-SA 2.0

From Budleigh Salterton parish records it is clear

that John’s death took place at Stiffkey, on the North Norfolk coast. An anti-aircraft

training camp and artillery range had been established south of Stiffkey

marshes in 1938 and remained in operation throughout the war. Another range

was established at Weybourne, further along the coast.

Stiffkey Artillery Range bye-laws (1938)

Stiffkey Camp and Range occupied a substantial

area and evidently caused some upset to local fishermen who protested at the

loss of their livelihood, access to the area at firing times being prohibited

by bye-laws under the Military Lands Acts. On 7 July their MP, Sir Thomas Cook,

drew attention to their plight in the House of Commons, asking the Secretary of

State for War, Sir Victor Warrender, whether he would arrange for compensation for

‘worm-diggers and others’ on account of their loss of trade. Needless to say,

he was fobbed off with the response that the question of compensation was being

investigated, but that no payment could be authorised pending the result of an

enquiry.

A Royal Artillery Light Anti-Aircraft gun crew with 40mm Bofors gun at Harstad, Norway, 14 May 1940. Image credit: Imperial War Museums

Along the edge of the salt marshes lay a long concrete strip with four static Bofors guns, each with its own predictor – an electrically-powered gadget which was designed to accurately follow the flight of the target, and thus constantly measure its angle of velocity.

RAF Langham-based Henley L3363 flies over Weybourne artillery range © IWM (RAE O-784).

Aircraft from bases like nearby RAF Langham would

tow flying targets – called drogues – over the marshes for the trainee gunners

to aim at.

Firing took place annually on the range in daytime from 1 May to 30 September on weekdays, and occasionally in the winter months between October and April. There was also night firing, which lasted until 2.00 am.

Royal Artillery veteran Frank Yates, in his wartime memoirs published by the BBC in 2005, recalls the camp as a bleak place, windswept and looking out over acres of mudflats and salt marshes. A collection of large wooden huts, inadequately heated by cast iron stoves, surrounded larger dining huts and a canteen. There was a permanent staff to look after the place and to cook and administer to the needs of the troops who were there for firing practice.

John died at Stiffkey, but we do not know the circumstances as yet. Was it illness? A road accident? Could it even have been enemy action? The Luftwaffe obviously knew the location of the artillery camp and range. Frank Yates recounts a rather comic episode from his memories – ‘an unbelievable event’ as he calls it – when four Stiffkey gunnery instructors, supervised by a Major Hardy, were caught unawares by an unexpected arrival.

A formation of Dornier Do 17Zs Light Bombers of the Luftwaffe, circa 1940 Image credit: Wikipedia

‘Our troop was next in line,’ as Frank Yates recalled, ‘standing

at the back, with Major Hardy telling the four instructors to “Show ‘em how to

shoot”. Picture the scene: four Bofors guns, all manned, four predictors, all

manned, each autoloader with a clip of at least four rounds of ammunition. The

target had disappeared towards the east, in the direction of Sheringham, and we

awaited its return. It didn’t come! Instead, a pair of Dornier 17s, one behind

the other, passed in front of us, on the exact course of the drogue. I saw the

German gunners staring at us as they passed! NO ONE DID ANYTHING! FOUR GUNNERY

INSTRUCTORS AND NO ONE DID ANYTHING! Major Hardy was dancing about on his

assorted legs and yelling “Get the b*****s, Why the f**k don’t you fire?!” A

minute later the target plane came along and the firing went on, as if nothing

had happened! The event was much discussed in the Sergeants’ mess. We decided

that the instructors had been so used to their sheltered existence that they

had forgotten that they were soldiers and sworn to fight the King’s enemies. It

was clear that such an eventuality had never been considered. If the crews of

the four guns had been told, that, in the eventuality of a hostile aircraft

coming in range, they could act accordingly and independently, the Dorniers

would have had a nasty shock.’

A 40 mm Bofors of 117th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment with gun crew under training at Billingham, County Durham, 21 January 1942. Image credit: Lt O'Brien, War Office official photographer From the collection of the Imperial War Museums

Perhaps more likely than enemy action as a cause of John’s death was an accident on the range. The 40mm Bofors guns of the type installed at Stiffkey had been designed in 1928 for the Swedish army and navy and by the mid-1930s the gun had earned a world-wide reputation for reliability and efficiency. It was adopted by the British Army in 1937 and a licence to manufacture the weapon in the UK was obtained. The Bofors’ accuracy and rapid rate of fire was particularly effective against low-flying or dive-bombing aircraft, making it a vital element in the air defence of Britain.

But occasionally there would be an issue, notably when a ‘misfire’ occurred because of damp powder failing to ignite the cordite explosive material in the shell. Frank Yates recalled the moment when official instructions were issued to gunners in order to deal safely with such an eventuality. A couple of weeks later, a message marked ‘URGENT’ arrived, ordering that the new misfire drill was to be abandoned immediately. Evidently the new drill had caused expanding gases to propel an exploding shell backwards, with tragic consequences for the gun crew.

Cyril Frederick Perkins was another WW2 Royal Artillery veteran who graphically described a mishap involving a Bofors gun at Brindisi in Italy, in 1944. He recalled for the BBC in 2006 how the commander of an artillery unit made the wrong decision when dealing with a stoppage in the firing, caused by a separated round of ammunition. ‘His gamble misfired. It takes four men to fix lifting gear and remove a Bofors barrel - twist and pull - lay the barrel on a rack and insert the waiting replacement. They never got that far - with the twist completed they began the pull - and at that point the projectile exploded. Two and a half hundredweights of rampant tensile steel lashing into soft yielding flesh was a no contest - two men were killed instantly and one other seriously injured.’

The thought of such an accident occurring at Stiffkey, resulting in John’s death, is awful to contemplate. But perhaps the circumstances were not so dramatic after all. However John lost his life, it seems that he was a popular member of his artillery unit, and that the grief felt by all on learning the news of his death was heartfelt.

Parish records mention a vase in connection with his grave. I

imagined that a china vase would have disappeared long ago. But looking at the

grave as I photographed it, I saw that the vase is actually a substantial piece

of granite. And it bears an inscription telling us that the vase was from Officers, Warrant Officers, Non-Commissioned

Officers and Men of 118th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment. It also has those artificial

flowers which look as if they were placed at the grave not too long ago. So

perhaps there are family members out there who can tell us more about John.

His parents – Ernest William and Alma Elizabeth Endicott, née Lake, were certainly living in Budleigh Salterton at the time of the death – at a house called ‘Southbrook’ according to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website. And that, presumably, is why John’s grave is here in St Peter’s Burial Ground.

The next post is for Private Stanley John Holloway (1914-41), killed by a landmine on 3 July 1941

You can read about him at

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2020/12/ww2-75-3-july-1941-our-beloved-son.html

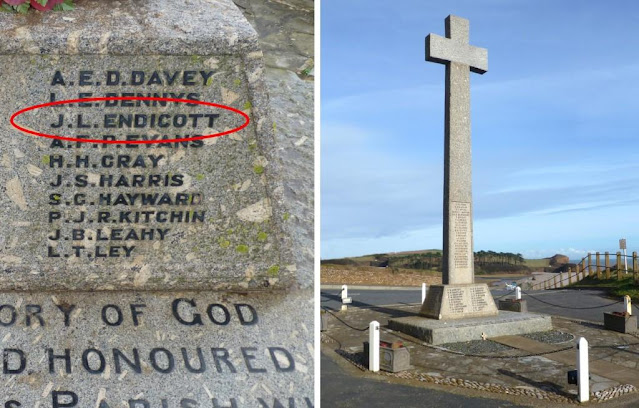

These ‘orphans’ are listed on Budleigh Salterton War Memorial, but have not been identified. Their first names, date of death and service numbers are not known. They are recorded on the Devon Heritage website as ‘Not yet confirmed’.

If you know anything which

would help to identify them,

please contact Michael

Downes on 01395 446407.

F.E. Newcombe

F.J. Watts

Comments

Post a Comment