Continued from 26 Jan 1942:

Fighting with ‘The Forgotten Air Force’: SERGEANT

DERYK VAUGHAN SAUNDERS (1920-42)

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2020/12/ww2-75-26-january-1942-fighting-with.html

Writing

about Budleigh and WW2 it’s impossible to ignore Joyce Dennys’ books, ‘Henrietta’s

War’ and ‘Henrietta Sees It Through’. Published respectively in 1985 and 1986, both

books are based on letters purportedly written by Henrietta Brown, the doctor’s

wife in a small Devon coastal town to her childhood friend Robert.

Front page of the 12 May 1915 issue, featuring

Rita Jolivet, British actress who survived the sinking of the RMS Lusitania. Photograph by Foulsham and

Banfield, Ltd.

The

letters are dated from 1939 to 1945 and were originally published in the ‘The

Sketch’, a glossy illustrated weekly journal, which focused on

high society and the aristocracy and ran for 2,989 issues between 1 February

1893 and 17 June 1959. They

reflect in a tongue-in-cheek way the goings-on and characters of the ‘Home

Front’ as people dealt with the daily challenges of World War Two.

An amusing Budleigh bathroom

mural by Joyce Dennys

You

could say that the ‘Henrietta’ books are a gentle and witty caricature of Budleigh

Salterton, as indeed are Joyce Dennys’ paintings. It’s always been easy to poke

gentle fun at our little town, as did Dennys’ friends and fellow-residents the

writers R.F. Delderfield and V.C. Clinton-Baddeley. And I won’t remind you of

what Noel Coward wrote in that play.

How

can one reconcile Joyce Dennys’ arch humour with such a grim and tragic

subject? Perhaps one should simply accept that her humorous style was just what

Britain needed to help maintain its stiff upper lip.

General Lancelot Dennys, right,

with General Archibald Wavell Photo courtesy of Nicholas Dennys

QC

Was

she really impervious to people’s personal tragedies? It seems unlikely: she

lost her much-loved brother Lance in an air crash in March 1942.

And

yet Budleigh is portrayed comically – far from the reality of the War. It’s true

that in her first letter of ‘Henrietta’s War’, dated 18 October 1939, she

writes: ‘Here we go on much as usual and one feels faintly ashamed of being in

such a safe area.’ But then, this was

the period of ‘The Phoney War’…

By

the time of the letters in ‘Henrietta Sees It Through: More News From The Home

Front 1942-45’, WW2 had become a desperate struggle for survival for Britain,

faced with the threat of Nazi invasion. Yet the country, it must have appeared to

many, was clearly divided between the hell of cities like London, Coventry and

Bristol and the relatively peaceful oases of small towns like Budleigh. Hence

the scornful view of the outsiders whom Dennys refers to as ‘the Visitors’; she

quotes in a letter of 25 February 1942 their bitter ‘What you all need is a stick of bombs to wake you up.’

Later in the book, in a letter dated 6

September 1944, Henrietta tells Lady B. that Londoners ‘are just a wee bit

cross with us for not having the Flying Bombs here.’

In

‘Henrietta Sees It Through’, Dennys succeeds beautifully in expressing the secret

hurt that many little oasis-like communities such as Budleigh were

experiencing. In the face of such mockery by Londoners and other ‘Visitors’, Budleigh

Salterton maintains its quietly dignified stiff upper lip, but inwardly

suffers: ‘Those people here whose homes have actually

been destroyed by bombs, or who have suffered loss and anxiety on account of

the war, take these remarks very much to heart.’

It’s in that letter of September 1944 that Joyce Dennys succeeds in combining high comedy and

deep pathos. The grief of a Budleigh couple – namely The Admiral and his wife

Alice ‘Mrs Admiral’ and their friends – is expressed in so understated a way,

with tiny gestures that say so much. Henrietta’s husband Charles is godfather

to the Admirals’ son Teddy.

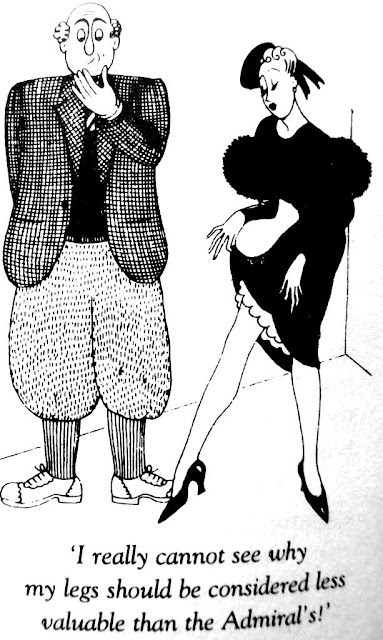

The Admiral and Faith, drawn by Joyce Dennys

The depiction of their grief is all the more

effective for being contrasted with how the Admiral has been previously introduced

to us. A letter of 3 June 1942 had focused on a Sunday morning discussion ‘charged

with sex-antagonism’ because only 95 people had voted for equal compensation

for women who get injured in air raids. Joyce Dennys’ drawing shows an embarrassed-looking

Admiral unable to answer the glamorous divorcée Faith’s challenging statement: ‘I really cannot see why my

legs should be considered less valuable than the Admiral’s!’

And in the following scene,

Henrietta Brown is no longer the timid, self-deprecating put-upon wife portrayed

by the author in her two books. When the Admiral turns up unannounced on

Henrietta’s doorstep she reacts instinctively. But let Joyce Dennys’ words

speak for themselves:

‘As soon as I saw his face I knew something

must have happened to Teddy, their younger boy, in France. ‘We’ve had bad news,

Henrietta,’ he said. ‘I expect you can guess what it is.’

Mrs

Admiral and Henrietta Brown

Henrietta

accompanies the Admiral back to his house, where Alice is frying some fish for

lunch:

‘She was quite calm, but her face looked

different. I put my arms round her and kissed her, and then took the frying-pan

out of her hand. The Admiral looked at us helplessly for a moment and then went

out of the room.

Mrs Admiral sat down on a kitchen chair and

picked up a corner of her apron and examined it closely. ‘I keep thinking about

him when he was a little boy,’ she said in a careful voice.

‘He

was a dear little boy.’

‘They

both were. It’s hard on their father, losing both his splendid sons.’

Then

there was a silence. I turned the fish over and there was a great spluttering. ‘Hake

does spit so,’ said Mrs Admiral. Then she said, ‘We’re not telling anybody,

because of the croquet this afternoon.’

The stiff upper lip. Croquet must go on,

especially in Budleigh Salterton. A ‘Daily Telegraph’ article from 2001 about

the town by journalist Simon Heptinstall mentioned his discovery in the local

museum of a

document entitled ‘The Croquet Club - The First Hundred Years’. The entry for September 1939 ran: ‘Sunday

afternoon play agreed. War declared.’

So the croquet went on, and Mrs Admiral insisted

on her croquet game arranged with the delightfully named Mrs Whinebite. Henrietta describes how some Visitors from the

hotel wander into the club and pause on the far side of the croquet lawn. Every

woman, notes Henrietta in her letter, feasts her eyes hungrily on the Lady

Visitor’s duck-egg linen suit.

‘My dear, croquet!’ said the Lady

Visitor to her companion. Then she gave a little scream. ‘Oh! And bowls, too!

How sweet! Of course, these people simply don’t know there’s a war on!’

The

Admiral dropped his pipe on the grass. As he stooped to pick it up he laid his

hand for a moment on Mrs Admiral’s knee.’

The next post (The Admirals’ Grief, Part ii) is for

Second Lieutenant John Barham Leahy (1920-42).

He was killed on 1 February 1942 in the Battle of Singapore.

You can read about him at

These ‘orphans’ are listed on Budleigh Salterton War

Memorial, but have not been identified. Their first names,

date of death and service numbers are not known.

They are recorded on the Devon Heritage website as

'Not yet confirmed’

If you know anything which would help to identify them,

please contact Michael Downes on 01395 446407.

F.E. Newcombe

F.J. Watts

Comments

Post a Comment