WW2 100 - 10 April 1940 - In ‘a corner of a foreign field that is forever England’: Leading Stoker Frederick William Richards (1901-40), Royal Navy, HMS Hunter

Continued from 23 November 1939:

Seaman Charles John Sedgemore (1916-39)

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2020/11/ww2-75-you-have-done-your-duty-nobly.html

Frederick William Richards' name appears on Budleigh Salterton's War Memorial

Frederick

William Richards died on 10 April, 1940, while serving on the destroyer HMS Hunter

during the First Battle of Narvik, fought off the coast of Norway. He was

one of 112 casualties in the battle, from which there were 46 survivors. Frederick’s

death was the first of seven Budleigh-linked losses in 1940, the second year of

WW2.

Frederick's original grave in Norway before he was moved to Ballangen Cemetery, maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Frederick’s name is recorded on Budleigh’s War Memorial, but he was born on 29 July 1901 in Ottery St Mary, and both his parents, Robert Edwin Richards and Ellen Richards, a Cornishwoman from St Austell, lived in Ottery. They died in 1949 and 1953 respectively and are buried in Ottery Cemetery.

A 1909-13 stoker recruitment poster from the days of coal power, showing what were supposed to be the attractive aspects of the job. The reality was rather different. Those stokers' overalls look very clean. Image credit: Imperial War Museum Collection © IWM Art.IWM PST 0805

As a stoker, Frederick was part of a group of crew members based in a ship’s engine room. They were, seemingly, much maligned over the years as an inferior class compared with other groups, quite wrongly in the view of a naval historian like Dr Tony Chamberlain. His 2013 University of Exeter doctoral thesis entitled ‘Stokers - the lowest of the low?' A Social History of Royal Navy Stokers 1850–1950 can be read online.

An officer

at the Unit Board in X Engine Room of the battleship HMS King George V,

commissioned in 1940 Image credit Lt S.J, Beadell Imperial War Museum Collection © IWM A 1783

The world’s navies’ reliance on coal in the pre-WW2 era

had declined in favour of oil as a fuel

for ships, meaning that engine rooms were cleaner. No longer did stokers have to shovel coal; their job in

keeping the engines running required more technical skills. Dr Chamberlain

quotes Stoker

Richard Rose’s observation that ‘you could go down the stokehole in an oil

fired ship in your Sunday best clothes and wouldn’t get dirty’.

A new type of stoker was needed, a requirement which even caught the attention of foreign media like the New York Times, which ran an article on 24 August 1929 under the headline ‘British Navy Seeks Stokers with Brains’. Recruiting officers were instructed to be careful that no man who appeared ‘dull-witted or unintelligent’ was entered for service.

As a Leading Stoker in 1940 Frederick was a skilled and experienced crew member and had joined the service in the pre-war period. His service number was D/K 57749. He started as a stoker with HMS Resolution, a Revenge-class battleship and the first of four ships, including shore-based training establishments, in which he served in the early 1930s.

Image credit: Derek Harper

Home for Frederick at this stage was the East Devon village of Farway, where he lived at 6, Hillside. It was at Farway that he married Marjorie Dorothy Sarah, the daughter of builder Harvey Clarke and his wife Jessie, who had settled in Budleigh but were originally from Peterborough and London respectively. The marriage took place on 16 April 1933, in the ancient parish church of St Michael, pictured above.

Fred and his wife Marjorie

Promotion to Acting Leading Stoker came later that year, on 6 November, and a year later he progressed to Leading Stoker while serving on the C-class light cruiser HMS Capetown. Further appointments in the 1930s included service on HMS Royal Sovereign and Revenge before the final post to HMS Hunter on 27 August 1939.

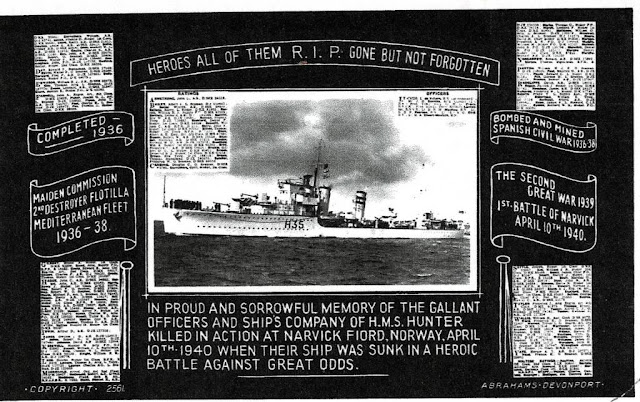

HMS Hunter Underway in Plymouth Sound Royal Navy official photographer. This is photograph FL 10190 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

Working in the engine room of HMS

Hunter, as Frederick did, in what was seen as the heart of the ship, was

still a source of pride for Navy stokers though the great age of coal had faded.

The spirit of camaraderie was particularly strong below decks. On the other hand,

in a sea battle the stoker’s position was particularly vulnerable. Not many

survived when a ship was torpedoed. 22 stokers, including Frederick, lost their

lives in the sinking of HMS Hunter in the First Battle of Narvik.

The ship had had an interesting history before Frederick joined it in 1939. An H-Class destroyer, it was launched in 1936, and in October that year sailed to join the Mediterranean Fleet at its base in Alexandria, Egypt. Malta, as part of the British Empire from 1814, had been the headquarters for the Fleet, but in 1935 the HQ had been moved to Alexandria due to the perceived threat of air-attack from the Italian mainland.

Attack by enemy submarine was also seen as a threat, and in the first week of September 1935 HMS Vernon equipped the Alexandria base with anti-submarine defences which included 192 mines, 150 miles of loop and mine cables and stowage for 498 miles of indicator loop and harbour defence ASDIC cable – ASDIC named after the Anti-Submarine Detection Investigation Committee.

In May 1937, Hunter was designated as part of Britain’s contribution to the League of Nations Arms Blockade and Non-Intervention Patrols, intended to help end the Spanish Civil War between the left-wing Republican government and General Franco’s fascist Nationalists, who were being supplied by Germany and Italy. Hunter’s captain, Commander Bryan Scurfield had no illusions about the value of his task, referring to the non-intervention scheme as ‘an absolute farce’. He also knew of the risks of being inside an active war zone, and was aware of minefields near where Hunter was stationed, off the Republican-held port of Almeria in Southern Spain.

Sure enough, on the afternoon of 13 May, a tremendous blast shook the ship, sending flames and steam shooting from the forward boiler-room and blowing away half the floor of the Stoker Petty Officers’ Mess. A mine, laid a month earlier by two ex-German Spanish Nationalist E-boats, the Requeté and the Falange, had detonated against Hunter’s hull, killing eight of her crew, including two stokers – Petty Officer Wilfrid Swiggs and Stoker 1st Class Alfred Waites.

In addition, 24 crew were wounded. The ship suffered severe damage, with a heavy list, her radio was wrecked and the bow flooded. Commander Scurfield at first considered abandoning ship, but Hunter was pulled clear of the minefield by the Spanish Republican destroyer Lazaga and eventually towed to Gibraltar, where temporary repairs were carried out from 15 May to 18 August. The ship was then towed to Malta for permanent repairs, but they were not completed until 10 November 1938.

The Albert Medal awarded to Lieutenant Commander Scurfield by King George VI

for his ‘gallant behaviour’ in the Almeria explosion incident www.vconline.org.uk

The incident had a serious effect on the morale of Hunter’s crew. If Frederick had been serving on the ship at this time it would be fascinating to learn, perhaps from a letter that he’d written, how he felt. He would certainly have lost friends in the terrifying blast. The recollections of a fellow-crew member, Seaman Marshal Grant Soult, recorded by the Imperial War Museums on 26 August 1991, give an interesting insight into life on board.

There was, Mr Soult told the interviewer, ‘a certain feeling about

the ship’ when he joined the crew of Hunter in 1938. He’d been told

about the incident of the mine, how all the seniors and older hands of the crew

had been in action at the time. He would have learnt of the heroism of Commander

Scurfield, who had been ‘on the spot in about ten seconds’, working ‘like a madman’

in the words of one witness as he pulled out wreckage which had trapped the cook

by his foot and hauled the man up to safety. ‘By his

gallant behaviour’ as the London Gazette of 2 July 1937 noted, helped by

a Lieutenant Humphreys and three Able Seamen, he saved the lives of Stoker

Petty Officers Lott, May, and Fenley; Stoker Neil; and Able Seaman Oliffe.

In one of the tragic ironies of war, incidentally, Bryan Scurfield was later captured and spent time as a prisoner-of-war. In April 1945, as he and a column of fellow-prisoners were being marched to another camp, six Allied fighters made a low strafing attack on the column, believing that the prisoners were German soldiers. Commander Scurfield died as a result of ‘friendly fire’.

Long after the explosion in 1937, explains Marshal Soult in the IWM recording, the crew of HMS Hunter felt ‘a certain pride’, the extent of which would create some embarrassment at the Mediterranean Fleet HQ in Alexandria.

For a crisis in the Mediterranean had arisen when Italy invaded Albania in early April 1939. Hunter’s crew were not happy at all on learning that the Admiralty had ordered the ship on further patrols of the area. They’d been expecting to return to Britain in March. Now they would be facing a further six to nine months at sea after the three years that they had spent away from home. Marshal Soult recalled the atmosphere on board ship as ‘very tense’, a situation which soon became clear to the Alexandria base authorities. In fact he describes in the IWM recording how he heard that marines on the base had been mobilised in case of trouble from Hunter’s crew!

Sir Alfred Dudley Pickman Rogers Pound, British

Admiral of the Fleet, First Sea Lord, head of the Royal Navy, June 1939–1943 Image credit: Bassano

- www.npg.org.uk

So tense was the situation that

the Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean fleet, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound

went on board to explain to the assembled crew how the ship was needed in the

area as part of his best anti-submarine division. Apparently, as recalled by Mr

Soult, a voice from the back called out: ‘We don’t want a lesson on Asdics. We

want to know what’s going on.’ Understandably, there were ‘red faces all round’

because the Admiral was accompanied by his staff.

It was usual in a Royal Navy tradition to give the Commander-in-Chief three cheers from crews of the assembled fleet as he left for home. Pound’s appointment to the Mediterranean Fleet ended on 31 May 1939. ‘He didn’t get many cheers from us!’ recalled Mr Soult. In fact, Hunter’s crew made its feelings clearly known when someone shouted through a loudhailer, ‘You’re going home. What about us?’

‘They never found out who it was,’ said Marshal Soult, explaining that it was a Leading Stoker who was on duty who came up through the hatch. ‘They had it all planned, I suppose... he died at Narvik anyhow, so they can’t have him for that now. Of the 22 stokers who were to die in the sinking of Hunter, four were Leading Stokers, including Frederick Richards.

In view of the damage caused by the mine explosion at Almeria, Hunter was sent to Plymouth for a more thorough refit in mid-August 1939, lasting until 27 August, when Frederick joined it.

Finally, the crew had some leave, recalled Marshal Soult. But only eight days’ worth: ‘everybody was a bit cheesed off’ when Hunter sailed, stopping briefly at Gibraltar before setting off for Freetown, in Sierra Leone, West Africa. On the way, on 3 September, war was declared. Late October saw Hunter transferred to the North America and West Indies Station, searching for the Graf Spee. The German heavy cruiser, famous later for being scuttled after the Battle of the River Plate in December 1939, had sailed into the South Atlantic two weeks before the war began, and had been raiding Allied merchant shipping.

An Atlantic convoy in 1942 Image credit: Wikipedia

Hunter’s duties, in its anti-submarine role, also involved escorting convoys of liners carrying Canadian troops, as well as one vessel which Marshal Soult remembered as ‘packed’ with explosives. It was a harsh environment, quite apart from the terrible weather. ‘If any ship was hit, you didn’t stop. You left them’.

February 1940 gave Hunter and its crew ‘the first decent leave’ that they had had for four years, the ship being given a refit at Falmouth that lasted until 9 March. It rejoined the 2nd Destroyer Flotilla of the Home Fleet at Scapa Flow a week later.

On 6 April Hunter and the rest of the 2nd

Destroyer Flotilla escorted the four destroyer minelayers of the 20th Destroyer

Flotilla as they sailed to implement Operation Wilfred, an operation to lay

mines in the Vestfjord to prevent the transport of Swedish iron ore from Narvik

to Germany. The mines were laid in the early morning of 8 April. News came the

following day that Narvik had been occupied by the enemy, and Hunter was ordered

to attack the town.

During what is known as the First Battle of Narvik on 10 April 1940, Hunter and four other H-class ships of the 2nd Destroyer Flotilla attacked the German destroyers which had transported German troops to occupy Narvik the previous day. The flotilla leader Hardy led four British ships in a surprise dawn attack on Narvik harbour during a blinding snowstorm. Hotspur and Hostile were initially left at the entrance, but Hunter followed Hardy into the harbour and fired all eight of her torpedoes into the mass of shipping. One torpedo hit the German destroyer Z22 Anton Schmitt in the forward engine room, followed by one of Hunter's 4.7-inch shells.

Nobody had seen Hunter in the dark, recalled Marshal Soult. He and the crew were ready for action: ‘We’d been trained for it all those years, and felt confident... Guns were firing everywhere... Ships were blazing and sinking. We thought we were having a ball.’

The British had hoped to capture Narvik, but in

retrospect, he felt that they would not have stood a chance against the enemy’s

hardened Alpine troops.

The wreck of HMS Hunter Image credit: Wikimedia

As the British ships were withdrawing, they encountered

five German destroyers at close range. Two of the German ships quickly set Hardy

on fire and forced her to run aground. Hunter eventually took the lead,

but was severely damaged by the Germans, probably including one torpedo hit,

and her speed dropped rapidly. Hotspur, immediately behind her, was

temporarily out of control due to two hits, and rammed her from behind. When

the ships managed to disengage, Hunter capsized. ‘Everybody in engine

room was killed,’ recalled Marshal Soult.

In total, 107 men of the crew were killed and another five died of their

wounds. The German destroyers rescued 46 men, who were released into Sweden on

13 April.

Ballangen Cemetery: Frederick’s grave is in the middle of the back row Image credit: www.cwgc.org

Frederick’s grave which you see here is in Ballangen Cemetery, in the town of Ballangen on the Vestfjord in north-west Norway, about 25 km south west of Narvik. The inscription on the headstone, requested by his family, has been used in the title of the story.

As I type, I feel that I have written the tale of HMS Hunter rather than Frederick’s, but perhaps such was the affection that sailors had for their ship that he would be happy with that.

It was good to be able to add to Frederick’s story with additional details, contributed later by a member of the family who had read my first version. On 8 March 1958, at The Temple Methodist Church in Budleigh Salterton, his widow Marjorie remarried. Her husband was Edward George Yeats, brother of Budleigh’s Ron Yeats, who had died in Normandy on 8 August 1944 while serving with the 1/5th Battalion, The Queen’s Royal Regiment (West Surrey) and the Royal Corps of Signals.

(Service Number 5334493), Royal Army Ordnance Corps, who was killed in action on 17 April

1940, in Northern France.

You can read about him at

These ‘orphans’ are listed on Budleigh Salterton War

Memorial, but have not been identified. Their first names,

date of death and service numbers are not known.

They are recorded on the Devon Heritage website as

'Not yet confirmed’

If you know anything which would help to identify them,

please contact Michael Downes on 01395 446407.

P. Pritchard

F.J. Watts

Comments

Post a Comment