WW2 100- 14 March 1942 - 'A born leader of men': Major General Lancelot Ernest Dennys, 1st Punjab Regiment, Indian Army (1890-1942)

Continued from 12 March 1942 – Flying with Kiwis

SQUADRON LEADER PETER JAMES ROBERT KITCHIN DFC (1917-1942)

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2021/01/ww2-75-12-march-1942-flying-with-kiwis.html

General Archibald Wavell (left) and General Dennys

Photo courtesy of General Dennys' grandson, Nicholas Dennys, QC

Only two Generals appear among the Budleigh-linked casualties

of WW2, and perhaps typically, both had Indian connections. The town had a traditional

connection with the subcontinent going back to the 19th century, as

I found when I wrote my little booklet about the Victorian scientist and sponge

expert Henry John Carter FRS, entitled The Scientist in The Cottage.

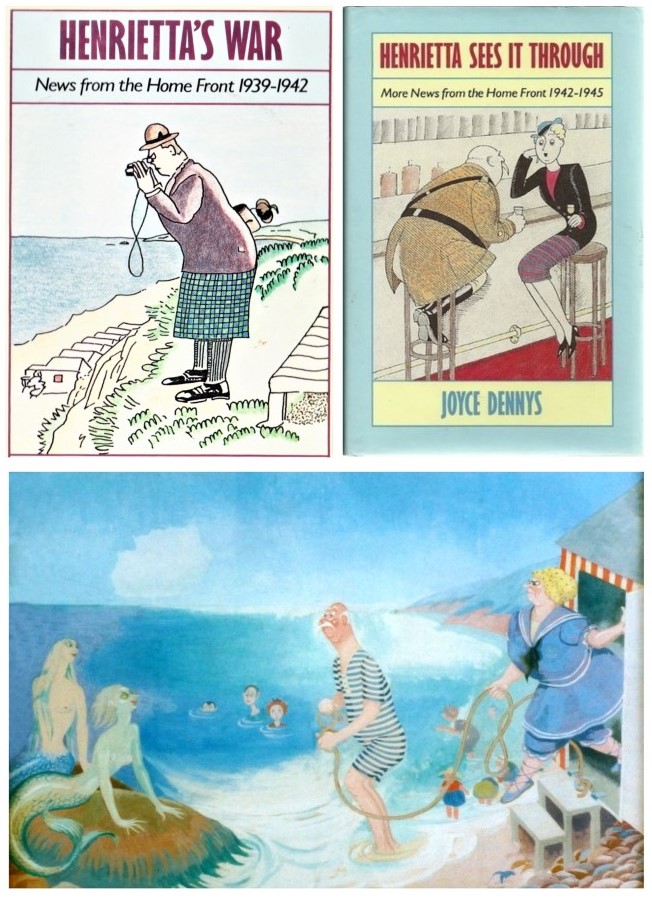

The books Henrietta’s War and Henrietta sees it through were published in the 1980s, based on humorous wartime letters written for The Sketch magazine. The painting above, showing an imagined Budleigh beach scene, was painted by Joyce Dennys as a bathroom mural

Of the two Generals, only one is listed on Budleigh Salterton

War Memorial. The other, General Sir Henry Finnis, has a more tenuous

connection. But Lance Dennys, as he was known to his family, may be recognised

by some as the brother of the artist and writer Joyce Dennys. Her paintings of local scenes, and her ‘Henrietta’

books based on our town during WW2, make her an integral part of any study of

life in Budleigh, and especially in the

1939-45 period.

So Joyce Dennys’ little autobiographical book And Then

There Was One provides us with an interesting and enjoyable background to a

certain group of characters who in many ways made Budleigh celebrated. The

writer R.F. Delderfield, a former local resident and friend of Joyce Dennys, wrote

in his own autobiography about these Anglo-Indians, so recognisable in the town

between 1860 and 1945, with their ‘hard blue eyes, fierce moustaches, and

mahogany faces’.

Like his sister, and other Budleigh residents such as the artist Cecil Elgee and Fairlynch Museum co-founder Priscilla Hull, Lance Dennys was born in India, where his father, Charles John Dennys, from ‘a well-known but impecunious Devon family’, as And Then There Was One puts it, was a Captain in the Indian Army. The military tradition in the family was strong, although Joyce Dennys in her book seems to hint that Captain Dennys was not very successful: in India ‘there was a lot of discipline which he didn’t take to,’ she writes. ‘He was constantly in hot water with various colonels and continued to be so until his retirement’.

But going back a generation was a different matter: ‘Both our grandfathers were Generals, which was a matter of pride to us’, she writes.

On their mother’s side there was the distinguished army medical officer Deputy-Surgeon-General John Tulloch whose origins she described as a mystery; his son – her Uncle Forbes – would tragically die of sleeping sickness after cutting his hand with an infected knife in Uganda.

General Julius Bentall Dennys, reproduced from And Then There Was One © Joyce Dennys

And on the father’s side there was General Julius Bentall Dennys, who served in the Bengal Army from 1840 to 1877. In 1891, in retirement at Sidmouth, he wrote his memoirs, entitled 'Some reminiscences of my life'.

Lance’s family: (L-r: back row) Mudzin (his mother), Ted (a cousin), Marjorie (his sister), Guy (his brother); front: Tippy (a cousin), Jub (real name Cecil, a cousin, Ted's brother), Joyce (his sister), Lance himself. Reproduced from And Then There Was One © Joyce Dennys

Lance’s family: L-r: Ted, Jub, Joyce and Lance himself.

Photo reproduced from And Then There Was One

No wonder, therefore, that many people thought,

typically for the time, that ‘Girls’ education was a small matter,’ as Joyce

Dennys writes ruefully. ‘The important thing was that the boys should get into

Sandhurst’.

St Bede’s, now known simply as Bede’s Prep School, Eastbourne Image credit: Theolimeister

But before that there was prep school. The Dennys family had returned from India to settle in Eastbourne, where Lance’s maternal grandfather Major General Tulloch was living, and both Lance and his cousin Ted went to St Bede’s which had been founded in 1895 in the East Sussex town with a roll of just four boys.

Eastbourne College

From St Bede’s, Lance progressed to Eastbourne College, entering Blackwater House as a boarder in September 1903. The College had been founded in 1867 by Dr Charles Hayman, an Eastbourne medical practitioner, as an independent school 'for the education of the sons of noblemen and gentlefolk' with the support of the 7th Duke of Devonshire. Lance was by all accounts a popular and enthusiastic member of the College, a House Prefect and highly regarded for his sporting talent in rugby and cricket.

He was also remembered

by his sister as a

member of the College Choral Society for his fine singing voice, as well as a

member of the Cadet Corps.

In 1904, Charles Dennys and his wife retired to Budleigh Salterton, renting what Joyce Dennys called ‘an unpretentious modern house’ and Lance spent his holidays in the town. ‘We had very happy holidays and were never at a loss for something to do’, recalls his sister. ‘There were tremendous walks and picnics and bathing in the summer. There were three beautiful old bathing machines on the beach in those days and a raft to dive off.’

Budleigh Salterton railway station: the white pebbles spell out ‘The West is

blest with Budleigh Salterton’. They were re-arranged regularly to give a

different message

The

journey by rail was remembered with nostalgia. 'At Budleigh Salterton

(which won prizes for its floral displays), one was greeted by the station

master as a friend.' (...) 'In those happy days

of travel one could step into a third-class carriage at Budleigh Salterton and

get out, calmly and unflustered, at Waterloo.'

Graduation Day: Passing Out Parade for another group of newly

qualified young officers, at The Old College Parade Ground, Royal

Military Academy, Sandhurst. Image credit: Simon Johnston

The Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst was still seen as the goal for Lance by his family, although as his sister recalls, his small stature was a worry. But by 1908 he had ended up just under six feet tall to everyone’s relief, and at Sandhurst soon showed the qualities demanded of a first-class officer. ‘He was a born leader of men, the natural commander, at his best and most cheerful in a tight corner or when any specially difficult or dangerous task had to be done,’ read his obituary in The Times. ‘On such occasions – and he always seemed to be on the look-out for them – he would give of himself without stint.’

Group photo of officers in the 54th Sikhs (Frontier Force) in 1912. Image credit National Army Museum, London

After passing out from Sandhurst, Lance served with the 1st Punjab Regiment in India, becoming an expert in mountain warfare through his experience on the North West Frontier of India. Promoted to Captain, his courage was recognised in WW1 with the award of the Military Cross and Bar. He played a prominent part in the capture of Sejarah Ridge on 20 September 1918, near Mt Ephraim in Egypt, while serving with the 54th Sikhs Frontier Force. British and Indian forces had been halted in their advance towards the Ridge after encountering heavy German and Austrian machine-gun and rifle fire which had begun to inflict serious casualties. Eventually, the 54th Sikhs succeeded in advancing between the pinned-down battalions and carrying the Ridge, though at the cost of 110 casualties, including Lance who was wounded.

‘He led his company through an intense cross machine-gun barrage and took his objective with the utmost determination and dash,’ read the citation, published in The Gazette of 8 October, the following year. ‘His personal gallantry and disregard of danger greatly inspired all ranks. Although severely wounded, he endeavoured to crawl and continue commanding, but finally had to be carried back by his orderly’.

By 25 September, in what became known as the Battle of Megiddo, described as a climactic event in the Sinai and Palestine campaign of WW1, German and Ottoman forces found themselves encircled by British Empire and French forces under General Sir Edmund Allenby.

The Razmak Gate, from the collection of the National Army Museum, London

Following the end of WW1 in 1918, Lance had a number of command posts, including with the Razmak and the Gurkha Brigades. The Razmak Brigade, an infantry formation of the British Army located along the North West Frontier, near Afghanistan was set up after the tribal uprising of 1919-1920. It was decided during the spring of 1922 to locate the main garrison of Waziristan at Razmak, and the self-contained cantonment, capable of holding 10,000 men, was established in January 1923. New roads linking the garrisons and camps in the area were constructed to permit speedier troop movements.

Major M.C. Holmes conferring with Afridi tribesmen, c1925. From the collection of the National Army Museum. The Afridi are a Pashtun tribe from the North-West Frontier area between Aghanistan and today’s Pakistan. Was Lance involved in similar discussions with local tribes?

Image credit: National Army Museum, London

Lance’s staff appointments in the post-WW1 period included General Staff Officer (GSO) with Military Intelligence at Army Headquarters (AHQ) at Peshawar on the North West Frontier in what is now Pakistan. British military thinkers of the 19th and early 20th centuries were endlessly involved in theorising about how units of the Indian Army could be trained to conduct successful operations on the North-West Frontier against the trans-border Pathan tribes. A Mountain Warfare School had been opened in May 1916 using innovative teaching methods specifically to train cadres of Territorial Army (TA) officers and NCOs in frontier fighting, who in turn would instruct their own units.

7th (Bengal) Mountain Battery going into action near Kaniguram, Waziristan, 1920. Oil on canvas by Ralph N Webber, 1984. This painting depicts Indian Army gunners leading mules carrying artillery and equipment up a hillside. From the collection of the National Army Museum

The 1929 competition organised by the Journal of the United Service Institute of India (JUSII) focused on modifications required to the existing doctrine of mountain warfare if the Pathan tribes were assisted by troops equipped with modern weapons, artillery and aircraft. It reflected a wider awareness of the problems likely to be encountered on the frontier in the event of operations against either regular Afghan or Soviet troops.

Lance shared the concerns. 'In future campaigns on the frontier we may encounter tribesmen, either equipped themselves with, or supported by other troops possessing modern artillery and aircraft,’ he wrote, as Major L.E. Dennys. ‘How can we best, both on the march and in bivouac, combine protective measures to safeguard ourselves against tribal tactics, as we have known them in the past, supported by such modern weapons.’ Quoted in ‘Passing It On: The Army in India and the Development of Frontier Warfare (1995) Timothy Robert Moreman MA (PhD thesis King’s College, London University).

Despite all the theorising by Britain’s military thinkers about how to quell the mountain tribes, the area remained troublesome up to WW2 and beyond. In what became known as the Waziristan Campaign, the British Army waged an unsuccessful war from 1936 to 1939 against Mirza Ali Khan, a mullah and so-called Fakir of Ipi who had united the warring tribes of the mountainous province of Waziristan. The government increased the number of both British and Indian troops in the area to reinforce the garrisons at Razmak and other towns near the Afghan border, but guerrilla warfare conducted by Pashtun tribes against the British continued and the Fakir of Ipi was never captured.

The Royal College

of Defence Studies, Belgrave Square, London Image credit: Wikimedia

By 1937, Lance had been promoted to Colonel and held a number of other staff appointments, including with Southern Command in Britain and at the Imperial Defence College – now the Royal College of Defence Studies – founded in 1927 to instruct the most promising senior military officers in the defence of the Empire.

At the outbreak of WW2, Lance was still in the Indian Army. However the British War Office was aware that the main theatre of conflict lay not on the North West Frontier of India, but further east. The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 had alerted Britain to a new threat to its Empire; the Sino-Japanese war which escalated from a dispute between Chinese and Japanese troops in 1937 was seen by many in Britain as foreshadowing WW2 in the Far East.

The Nanjing Massacre of 1937-38 was one of the most horrific episodes of the Sino-Japanese War, when soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army murdered disarmed combatants and Chinese civilians. In 1946, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo estimated that over 200,000 Chinese were killed in the incident. China's official estimate is more than 300,000 dead based on the evaluation of the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal in 1947. Above, the corpses of massacre victims lie on the shore of the Qinhuai River with a Japanese soldier standing nearby. Image credit: Wikimedia

The Japanese scored major victories, capturing Beijing, Shanghai and the Chinese capital of Nanjing in 1937. After failing to stop the Japanese in the Battle of Wuhan, the Chinese central government was relocated to Chongqing in the Chinese interior. With the strong material support through the Sino-Soviet Treaty of 1937, the Nationalist Army of China and the Chinese Air Force were able to continue putting up strong resistance against the Japanese offensive. By 1939, after Chinese victories in Changsha and Guangxi, and with Japan's lines of communications stretched deep into the Chinese interior, the war reached a stalemate. Japan ruled the large cities, but it lacked sufficient manpower to control China's vast countryside. In November 1939, Chinese nationalist forces launched a large scale winter offensive, while in August 1940, Chinese communist forces launched a counteroffensive in central China.

Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist Chinese

Against this background, in November 1940, the British War Office transferred Lance from India to the Chinese wartime capital Chungking, to serve as military attaché to China. In January 1941 he reached Chungking and began ‘unobtrusive’ discussions about mutual assistance. With the help of the RAF's Air Attaché in Chungking, James Warburton, Lance fostered relations between the British and the Chinese, notably with the Nationalist leader Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek: airpower as well as guerrilla warfare was to be a major element of Anglo-Chinese military cooperation. At the end of February he recommended that a small military mission be set up in Burma which would eventually move into neighbouring Yunnan when war broke out between Japan and the British Empire. Lance was responsible for forging a Sino-British agreement whereby British troops would assist the Chinese ‘Surprise Troops’ - units of guerrillas already operating in China, and China would assist Britain in Burma.

Captain, later Lieutenant Colonel, Mike Calvert, with whom Lance was working on 204 Mission, is pictured above, third from the left. Centre is General Orde Wingate, creator of the Chindit special forces in Burma. Like Lance, Wingate was killed in an air crash during the war. Photograph MH 7873 from the collections of the Imperial War Museums.

In December 1941, Japan finally entered WW2 with the bombing of Pearl Harbour and the invasion of Singapore and Malaya. It was time for the launch of 204 Mission, or Tulip Force, as it was also known – the culmination of Lance’s plan to provide military assistance to the Chinese Nationalist Army in order to sustain resistance to the Japanese occupation of China. During the previous months of October and November, a small group of Australian soldiers from the 8th Division, including two officers and 43 men, had been posted to Burma. There they had been trained in demolition, ambush and engineering reconnaissance at the Bush Warfare School, run by Captain Mike Calvert. In addition to the Australians, Tulip Force also consisted of a number of British troops.

Australian members of the first phase of Mission in Yunnan Province, China in 1942

The men departed in February 1942, the first phase consisting of three contingents, two British and one Australian, each of 50 army commandos. They travelled up the Burma Road in trucks for nearly three weeks before crossing into China, covering more than 3,000 kilometres (1,900 miles). From there they travelled another 800 kilometres (500 miles) by train into China, before traversing the mountainous border region to join Lieutenant-Colonel Chen Ling Sun's Chinese 5th Battalion. They brought with them large amounts of equipment, including explosives.

The Douglas DC-2 aircraft which crashed, killing Lance and 12 other passengers. Image credit: Bureau of Aircraft Accident Archives www.baaa-acro.com

Disaster struck Mission 204 in its early stages on 14 March 1942. Lance and a group of military and other advisers, some of them American, were on board a Douglas DC-2 aircraft with a crew of three, on their way from Kunming to the Chinese Nationalist capital of Chongqing. Shortly after take-off from Kunming-Wujiaba Airport, one of the engines failed. The aircraft stalled and crashed in a field located two kilometres past the runway end. Four passengers were rescued but 13 other occupants were killed, including Lance.

On board with Lance, among the fatalities, were individuals who had no doubt been involved in the planning of Mission 204. They included officers Lt Col Frederick L. Kohler and Lt Col Otto C. George from the US Military Mission. There was also an economic adviser Dr. Fenimore B. Lynch, Financial Director of the Central Bank of China. Survivors included Col Harvey Edwards, employee of the American President Roosevelt's mission. Lance’s wife, Eileen, was in Chongqing at the time of the accident.

Lance’s death was certainly a major setback to Mission 204. It later ran into difficulties which at least one historian believes he would have been able to overcome, such was his commitment to the project.

The Sai Wan War Cemetery, Hong Kong and the headstone of Lance’s grave

Image credit: NickD and www.findagrave.com

Lance was buried at the Sai Wan War Cemetery on Hong Kong Island, and of course is remembered on Budleigh’s War Memorial. This profile has turned into a bit of an epic, but I thought that he had such an important role in WW2 that just a name on a monument was not enough.

And if you’ve come this far, let’s end with a ‘What if...’

What if Lance had survived the air crash and gone on to make Mission 204 a success, enabling the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek to defeat not only the Japanese but also the Communist Chinese under Mao Zedong? China today might be a very different place!

Budleigh Salterton's War Memorial at the junction of Salting Hill and Coastguard Road

The next post is for PILOT OFFICER JOHN ALASTAIR SEABROOK (1920-42) who was killed on 10 July 1942 while serving with the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve in 250 Squadron

You can read about him at

https://budleighpastandpresent.blogspot.com/2021/01/ww2-75-10-july-1942-his-last-flight.html

These ‘orphans’ are listed on Budleigh Salterton War

Memorial, but have not been identified. Their first names,

date of death and service numbers are not known.

They are recorded on the Devon Heritage website as

'Not yet confirmed’

If you know anything which would help to identify them,

please contact Michael Downes on 01395 446407.

F.E. Newcombe

P. Pritchard

F.J. Watts

Comments

Post a Comment